Spoilers!

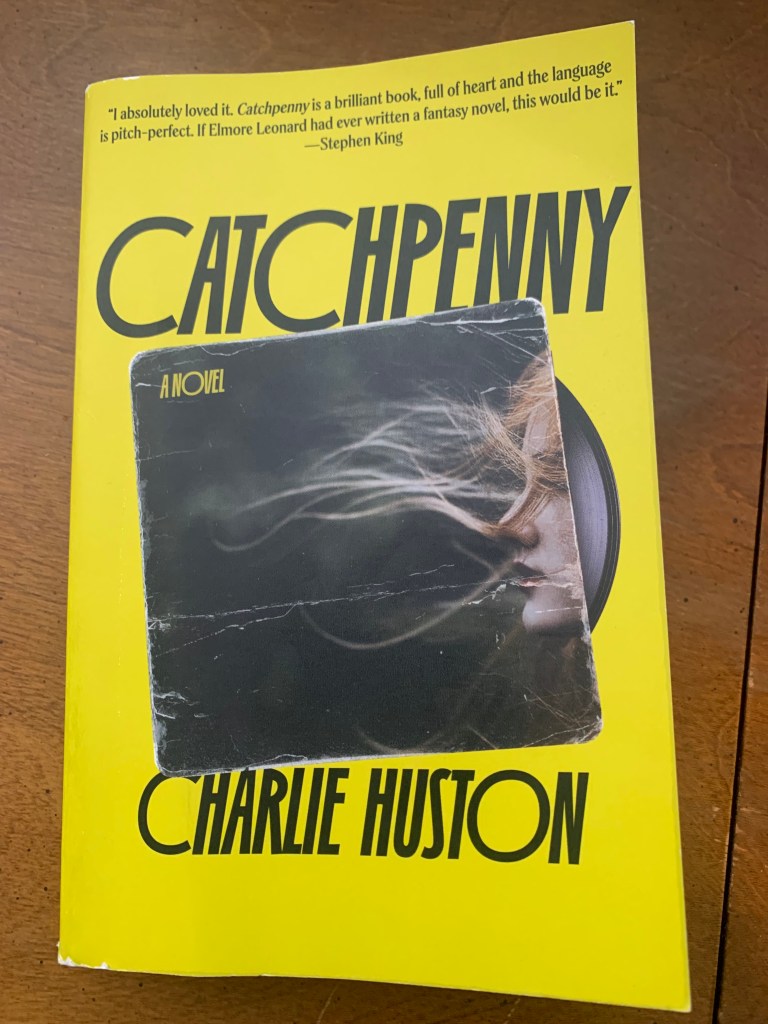

IRL. In real life. When the internet was first blossoming, there was a sense of a distinction between what happened “in real life” and what happened in cyberspace. I’m not sure such a distinction makes much sense anymore. In his 2024 novel, Catchpenny, Charlie Huston obliterates the divide, if it does still exist, with a fantasy-punk-magical realism story featuring the power of Sinéad O’Connor, manikins (like mannequins), and mirror travel.

Sid Catchpenny is a thief without a heart (literally) and his beautiful voice (literally), selling both off for revenge, a poison that only seems to be affecting him, as he’s been mired in depression for most of his life. His wife and unborn baby were killed by … himself, or rather, a manikin of himself. In the 30 years since, he’s jumped into the “racket” of accruing (stealing) “curiosities,” i.e. objects and things that have mojo. Mojo is the magic all around us imbued by our passions, wants, hates, and fears. Those within the racket, like Sid, are able to set “courses” to channel that magic to move through mirrors — which assists with the thieving —, to make the manikins, often for security, and to accumulate more power. It’s a loop, or like the book’s cover with the stylized circle in “novel,” a circle. You get into the racket to learn magic to accumulate more power to use more magic to accumulate more power.

The one item Sid has left from Abigail, his love and would-be mother of his baby, is her Sinéad O’Connor T-shirt, featuring the cover art from her debut 1987 album, The Lion and the Cobra, which Huston himself used to get through tough times. Sid’s depression predates Abigail, but it certainly wasn’t helped by her seeming murder. Turns out, according to the manikin, she killed herself instead of dealing with her head-in-the-clouds, aloof husband and the obvious fact that he didn’t want a baby derailing his rocket to stardom.

But that’s all later. First, Sid is thrust by his longtime friend, Francois, into the mystery of Circe, a 15-year-old girl who has gone … gone. That’s a nice bit of clarification from her mother, Iva: She’s not “missing” like your car keys are missing. She’s gone. In the course of the afternoon and night over the length of the novel, Sid will be accosted, beaten, escape de fact custody from the “assholes” who control all the magical power, betrayed, and unravel the mystery of not just the suicide cult that ensnared Circe, Francois, and Iva, but the aforementioned story with Abigail and his manikin.

Real life is not real life; it’s just what we’ve constructed as reality. Through the mirrors is nothing and everything. Reality and not reality. Something and nothing. The internet is supposedly where mojo goes to die, which is why the old timers in the magic racket hate smartphones, the internet, and Big Tech. The mojo can’t be harnessed until it can be because if nothing is real and everything is real, then there being rules and no rules around magic (the two most unbreakable not-rules rules are that magic can’t enable you to time travel or resurrect the dead) is a faulty premise. The child of a suicide cult leader, Carpenter, figures out how to harness, or course, the mojo from an internet game he created. I’m not quite sure what his end game (heh) was with it, but it goes to the point at the top of this review. What we put into the internet — through social media, blogs, video games, etc. — exists. It’s as real as the empty Gatorade bottle sitting next to my laptop as I type this. Why would we ever have made a distinction between these words in cyberspace and the fact of that bottle? We certainly know what comes out of the internet can affect us in the same way something “in real life” can, i.e., words can hurt. Or seeing a sad or happy video while we’re scrolling. Real and not real.

Circe’s aim is not dissimilar to a lot of people on the fringes of politics (left and right). She wants to destroy the world to remake it anew in her vision of the world. Her vision of the world is one in which the magic that has accumulated to the 1 percent, as it were, is disseminated to everyone and used by everyone, with the caveat that to use magic, one must do something selfless. With the help of Sid, who goes through his own character development arc of at first not caring about a seemingly random girl, to caring inasmuch as it’ll allow him access to use her room filled with mucho mojo, to finally helping Cerce because it seems better than the alternative, with no personal motive necessarily in it for him, Cerce achieves her aim. Magic is for everyone. The system is upended, in good ways and bad. Even with fame and magic, Circe still has to advertise lotion on the internet to pay the bills. Heh.

The saddest fact of the book is that Iva, whose father is Francois, tried to shield Circe from magic because of what Francois’s obsession with using magic to protect Iva did to her only for Iva to “imprison” Circe in a similar way and Circe to rebel in a similar way Iva did. Or maybe the saddest fact is that when Francois and Sid needed each other the most (Francois to rescue Circe from the suicide cult and Sid to survive his depression), they couldn’t find the language to help each other. I also thought Huston described Sid’s depression accurately throughout the book. Depression is that force which is reality and not reality, too. It causes “in real life” pain, and is not real as an accurate reflection of our lives.

Huston’s book ends on a cliffhanger. Sid, who is somewhat akin to an antihero, is going back into the nothing (or something) of the mirrors to rescue Francois, which is supposed to be impossible. Impossible and possible. Reality and not. Rules and no rules.

Like Sid being drawn to a mirror, first out of vanity and then out of survival and later, for heroism, I was drawn to Huston’s fantasy-mystery book. He took what at first appeared to be shattered pieces of a mirror, where you sense things are connected while being disconnected, and put them all back together nicely to reflect a well-told, well-developed, and well-paced story, with a healthy balance of heft and levity. There is so much more I can say about the plot and the themes of Catchpenny, but it’s better to be experienced, felt, and surfaced when read.