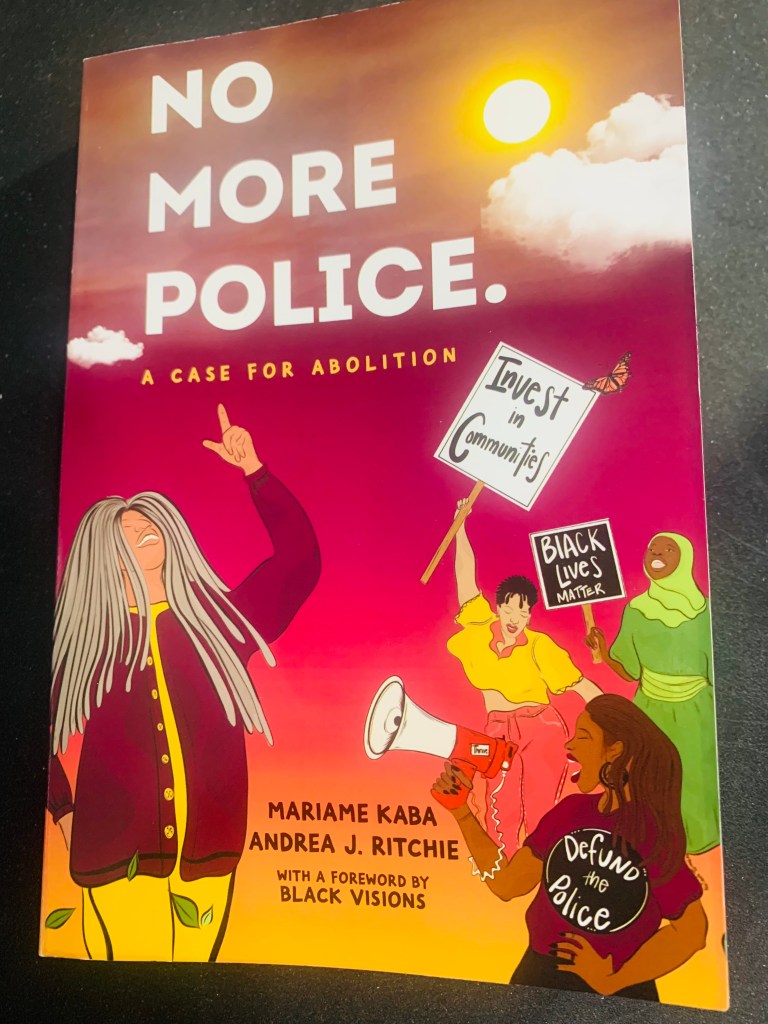

There are three things you cannot say about those who made calls to “defund the police” or more precisely, abolish the police (and the criminal justice system, or as they more accurately refer to it as, the “criminal punishment system”) in the wake of the George Floyd killing, or the 2020 Uprisings, as movement activists call it: 1.) That it was their first time calling for such a solution, as abolitionists had been working in that space, and even in Minneapolis where the killing occurred, for years, even decades, prior; 2.) That they haven’t extensively thought through the what, why, how, and then what of abolition; and 3.) That there aren’t a wide array of grassroots organizations, nonprofits, mutual aid groups, violence interventionists, and so on, that have been doing the work in communities experiencing violence (and violent police) for decades, already providing the groundwork for a world without police and the criminal punishment system. After the George Floyd killing and the 2020 Uprisings, I think all three criticisms were uttered in some form or fashion by politicians, pundits, and the public: this “slogan” came out of nowhere and was opportunistic after the death of George Floyd; the activists haven’t thought “defund the police” through and it’s naïve at best and dangerous at worst, and it turns off the public (in fact, it put abolition into the mainstream for the first time); and perhaps the most common refrain any time police are violent is “what about crime in your community?” In Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie’s 2022 book, No More Police: A Case for Abolition, the two movement activists and Black feminist abolitionists fully flesh out the three things you can’t accurately say about abolitionists (in response to what people are always saying about those who protest police violence), and they make a compelling case for police and by extension, all forms of government policing, including imperialism and war adventurism abroad, border control, and the many ways policing permeates other facets of society, including at hospitals, schools, and through child protective services organizations, or what Kaba and Ritchie refer to as, “family control,” through “soft policing,” to be abolished, as well as our punishment apparatus known as the criminal justice system.

Something I ran into when I was in college was the folly of reform as it regarded rape and sexual assault on campus. That is, you can’t reform a system that, as Kaba and Ritchie would argue with respect to policing, is working as intended. In other words, after researching the issue of the university’s response to rape and sexual assault on campus, that going back for years, at least into the 1990s, the university had convened task force after task force after task force to address the issue, and yet, years later, nothing meaningful had changed (except perhaps more money going to administrators). Kaba and Ritchie convincingly outline how the same is true of American policing going back more than a century: task forces, both at the federal, state, and local level, supposedly independent civilian commissions, and of course, federal consent decrees, have all occurred at one point or another across the country and with varying degrees in police departments, as well as federal reports on policing with a slew of recommendations for reform. And yet.

Reforming the police is a tempting mindset, one Kaba and Ritchie admit to embracing at various points. I, myself, have embraced it. The idea being twofold, I think, at least for myself: 1.) We can make policing better if we just implement X, Y, and Z, including better technology via body cameras, which Kaba and Ritchie compellingly take to task the idea of technology saving us from bad policing; and 2.) To shift the Overton window, as it were, to at least get those who currently favor the status quo with policing to at least embrace some sort of reform efforts that move us to less violent outcomes. I used this tactic a lot, especially as it concerned race. My motive was, hey, I will take race completely off the table, so, will you now embrace these reform efforts? It wasn’t effective, though, because even with race off the table — the idea being, people were perhaps getting distracted by that aspect of the discourse — people, not surprisingly, still didn’t want to embrace police reforms. Because to them, policing is working as intended for them, and if it’s not, then, as Kaba and Ritchie point out, the mantra is always “more funding for more cops and more technology and more community policing.” That is government in a nutshell: If it’s not working, throw more money at it; if it is working (or seems to be), better throw more money at it to ensure it continues to work.

And naturally, Kaba and Ritchie talk about how there was an intense backlash to the “defund” movement in the wake of Floyd’s death, where fearmongering was abundant, including from the Democratic president, no less, to fund police because crime was supposedly going up (not really), and specifically going up in places where police budgets had been slashed (not really, since budgets weren’t slashed!).

On the criminal justice system front, or prisons, Kaba and Ritchie making a moving argument for our system, indeed, being one about meting out punishment rather than ensuring accountability for wrongdoing, and whether the former serves the interest of lessening violence in society (it doesn’t, they rightly argue). Prisons, including because of prison guards, are also rife with violence and sexual assault. Kaba and Ritchie don’t accept such punishment for killer cops, either. That is how ardent they are in their beliefs. It’s admirable because if you start making exceptions in your abolition, then you don’t actually believe in abolition. It’s like the people who argue against the death penalty except for the really bad crimes. Well, then you’re for the death penalty. It’s that simple. This accountability paradigm versus one of punishment is what Kaba and Ritchie call transformative justice, a nonpunitive response to harm and violence. It seems like such an obvious reframing: Instead of using more violence in response to violence, they … don’t. They quote Mia Mingus, founder of the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, who states, “TJ is not simply the absence of the state and violence, but the presence of the values, practices, relationships, and world that we want.” That’s Mingus’ emphasis. People hear abolition and automatically think, as Kaba and Ritchie rightly bemoan, “What will be the police alternative then?” and think of it as an absence to be filled. In many ways, its tantamount to what happened after the American Civil War: Abolition of chattel slavery won the day, but it would be sort of odd to be like, “And replace it with what?” Instead, it’s about, as Mingus said, the presence of the world we want where African Americans aren’t enslaved anymore. Where American failed is we didn’t build that world by seeing Reconstruction through. Instead, we did indeed find an alternative to slavery that was very similar to slavery. Kaba and Ritchie rightly do not want that to happen, which is also why they are skeptical of soft policing, counselors, diversion programs, drug treatment courts, and the like as “alternatives.” Because, in form or another, they still amount to “controlling and containing” the undesirables, shifting them with “someone else” to “somewhere else,” as Kaba and Ritchie aptly put it.

I should back up. Kaba and Ritchie’s work is largely already in my wheelhouse, which is to say, I’m already a believer in the premise, promise, and practice of abolishing the police and the criminal justice system. My ideology is rooted in free market libertarianism and anarchism. I’ve written extensively about policing and the criminal justice system, with a flashpoint being Michael Brown and Ferguson in 2014, but prior to then, too. I especially appreciate the areas in which I thought Kaba and Ritchie’s work from a Black feminist abolitionist lens overlaps with my understanding of free market libertarianism, primarily in a.) abolishing the police and the criminal justice system, which includes a strong anti-war stance and anti-border and migrant enforcement stance; b.) necessarily then, against areas of life that are criminalized currently, including occupational licensing (that is, criminalizing those for performing activities, like braiding hair, without a license), the sex trade, the allowance for street vendors, the mentally ill with force institutionalization, police in schools, hospitals, and so on; c.) even those who have criticized COVID-19 policing will find common ground with Kaba and Ritchie, who are against how it worked because of how it became yet another reason to disproportionately target marginalized communities; and d.) it is inevitable that when you dip your intellect into the pool of abolition of the state’s monopolization on the legitimate use of force (police) and punishment (the criminal justice system), that will lead to questions about the very existence of the state itself, which Kaba and Ritchie richly dive into. In other words, another criticism of movement activists, particularly abolitionists, is how can they say one arm of the state (the police and the criminal justice system) is irredeemably white supremacist, but then seek the very same state’s help in areas they deem worthwhile (public schooling, healthcare, housing, etc.)? As I was reading the book, I was thinking a similar thought: Reforming policing is rightly considered a futile effort by Kaba and Ritchie, but reforming the state itself is possible (which also has the same problem of “if only we can get the right people in place” as policing reform does)? Well, Kaba and Ritchie’s response, thankfully, is largely, we can provide public schooling, healthcare, housing, etc., outside of the state. And in the short-term, we should reallocate the $100 billion annually spent on policing in the United States to those endeavors. Which is another area where pragmatic free market libertarian anarchists overlap with Kaba and Ritchie: believing that on the way to abolition of the state writ large, we should do the best we can, indeed all we can, for the least among us, the most marginalized and the worst off. In fact, some libertarians and anarchists, including myself, have flirted with the idea of a universal basic income instead of the welfare state, which Kaba and Ritchie worry has too many conditional strings placed upon who is “deserving” of it.

Overall, it is worth emphasizing that Kaba and Ritchie think too much of society, particularly as it comes down upon Black, Indigenous, trans, LGBTQIA+, disabled, migrant, and low-income/no-income persons, criminalizes behavior precisely because policing is not about “serving and protecting,” but rather, as previously mentioned, “controlling and containing.” The less we criminalize in the intermediary, the less opportunities there are for police interactions. The less we criminalize in the intermediary, the more communities can look to solutions that don’t require calling the police to intervene and potentially make a nonviolent situation more violent. And indeed, Kaba and Ritchie rightly attack the notion of “criminality” at all, both what is considered criminal, but also what is considered violent. What flows from that is then how to accurately assess violence and nonviolent “crime” in America, which spoiler alert, is a fraught exercise, both overstated and understated in equal measure (overcriminalizing and underreporting, respectively). But as we see, more money, more personnel, and more resources is always the answer when it comes to policing’s repeated failures to prevent and solve the most serious crimes, and no matter what the fluctuations in the statistics state. Even something that seems readily acceptable, as far as that goes, like the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, which I also believe Biden was a strong backer of, is criticized by Kaba and Ritchie for merely being another vehicle of police funding creep over the years, and which certainly doesn’t prevent violence against women (again, police rarely arrive on the scene of a violence crime to prevent or mitigate it, or to arrest the offending party or parties), and is actually damaging to survivors of violence, either by dismissing them (causing underreporting) or criminalizing survivors. The question for Kaba and Ritchie, and the rest of society, arises: Why do we continue turning to police as the one solution for violence and sexual assault? Indeed why, when often, police both in their profession and private lives, are just as guilty of violence and sexual assault, but also because it hasn’t worked for nearly 40 years. Kaba and Ritchie would rightly argue that the magical thinking is not abolition, but that we can make policing work despite decades of trying reforms, more funding, more personnel, more technology and resources without success in the stated aim to solve and/or reduce and/or prevent violence.

The one area I do disagree with Kaba and Ritchie’s thorough and considered analysis is their criticisms of what they call “racial capitalism” and their endeavor to also abolish that system, which they think the state props up. My issue with that analysis is first, much of what they are criticizing and trying to dismantle concerns the state and its monopolization on the legitimate use of violence and punishment. Yes, that intersects with capitalism inasmuch as crony capitalism manifest through firms (and people, including the fraternal order of police organizations throughout the country who are the ugliest in their abjection to any meaningful reform, or “police unions”) vying for the power of the state to wield it in a way that benefits them, including through profit. But the root problem is the state and its considerable monopolistic power, not profit itself. Relatedly then, and to my second point of contention with the analysis, is that I think what I prefer to call the free market, is a great benefactor, not a hinderance, to liberation from the state, its power, and indeed, its monopolistic violence disproportionately concentrated against marginalized and oppressed individuals. Far from being a centralizing force of exploitation and deleterious individualism, the free market is all about mutual cooperation and peaceful exchange, which is at the heart of abolition and the presence of mutual aid societies and other community-based organizations. Kaba and Ritchie rightly point out the problem with the misallocation of $100 billion to police agencies across the United States instead of to causes they deem worthy, but I would push the analysis further: That is precisely the problem with the state! It is a fight over the allocation pie, whereas the free market has no such pie, no zero-sum gamesmanship to it since humans are wealth-generators and we possess the greatest renewable resource known to Earth and mankind, our brains, enabling us to create an infinite number of diverse pies for everyone.

All of this is to say, when I marry my own precepts and ideology that brought me to abolition with the vision Kaba and Ritchie describe in No More Police sans the anti-capitalist take, I see a beautiful future of a better world with more peace, more abundance (something Kaba and Ritchie want), more cooperation, more community, and a better quality of life for everyone. But, and this is important, what I also love about Kaba and Ritchie’s treatment of abolition and paving the path forward, is that they lean into disagreements and dialogue with others. There is no hegemonic abolitionist vision, not among Black feminist abolitionists like them, and not among other abolitionist movement voices, and certainly, of course, not with abolition-friendly folks like libertarians/anarchists. However, as I’ve outlined, there are many areas of agreement in which to move to that better world. As I always like to say, we want the same thing, and in this case, we largely agree with the means on how to get there, but we do have a disagreement about what the fulfillment of abolition might look like (and fulfillment is for lack of a better word because Kaba and Ritchie rightly point out that abolition is an always-in-progress project, with mistakes and failures, fruits of experimentation, along the way to learn from), but that’s fine! My vision of a free market anarchistic society would certainly, obviously allow for those who don’t believe in capitalism to exist and build their own version of society. And I say that even though Kaba and Ritchie believe that abolition and racial capitalism are not able to coexist. Maybe they’re right with their analysis of capitalism, as they understand it, though. Maybe we agree more than we think since I skew more to the framing of the free market/free exchange of goods and services and ideas versus capitalism as typically understood.

Nonetheless, that potential disagreement aside, I found Kaba and Ritchie’s book well-reasoned, well-researched, and well-argued. Yes, I’m already a convert in many ways, but I couldn’t help but be moved, inspired, and captivated by the myriad ways movement activists like them have long-been doing the work and continue doing the work to build a future beyond, outside of, and after policing and the criminal justice system is abolished, and as I’ve said, often without any recognition or notice by those who think that work isn’t even happening (but I do think they overlook it in bad faith). After all, Kaba and Ritchie’s point is that abolition isn’t absence, but rather the presence of all the positive community-based solutions (and they are even hesitant to render “community” itself a panacea) to make a more peaceful, nonviolent, abundant society that respects all people and lets all people live their truest, best lives. Kaba and Ritchie put the onus, as it ought to be, on those who believe we need policing, and indeed, more policing, to explain why and how that is going to solve the root causes of violence and other interpersonal issues instead of non-policing solutions. They (the “police preservationists,” as Kaba calls them) don’t want that onus, which is why they strike back in paranoia any time policing is questioned in the United States.

If you’re even somewhat curious about this topic, I would highly encourage you to check out their book. If you’re already converted like me on the topic of abolition, you’ll still find this book useful for how to think through the issue in all its many facets. Kaba and Ritchie made me think and question myself, which I always appreciate.