Spoilers!

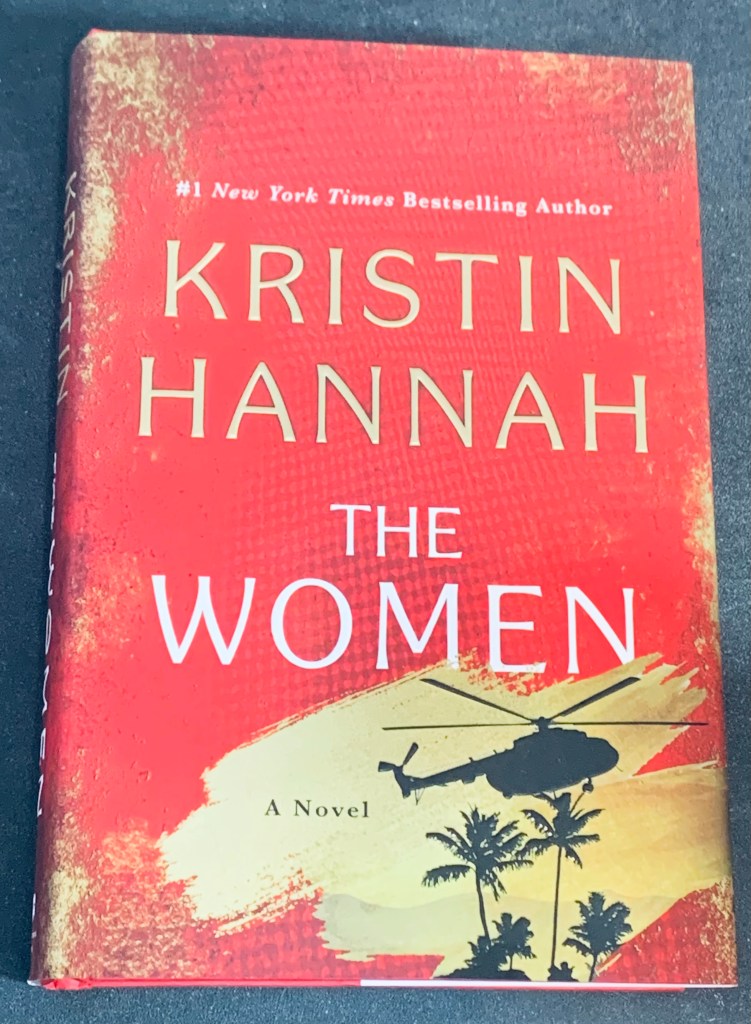

There were no women in Vietnam. There were women who served in Vietnam, and Kristin Hannah’s 2024 book, The Women, announces in a tour de force, They were over there. War is such a complex, nearly unfathomable machination of human life, and with it comes ripple effects long after the hostilities end, back on the domestic front, and within the psyches of those who experienced it. Even when the war seems over, and the experiences and the memories are aged with time, war comes back like the tide, bringing all the debris of yesteryear with it. Hannah added into this toxic tide the reminder of how the women of Vietnam were forgotten, generating another layer of trauma the women of The Women face.

Frankie is metaphorically knocked asunder when she realizes, thanks to a friend of her brother’s, Rye, that women can be heroes, too. That leads her to voluntarily join Vietnam, as a nurse, with the Army since other branches wouldn’t take someone without two years of experience. She’s thrown into the shit, red grime, and bloody catastrophe of Vietnam with limited experience, and more importantly, the ignorant and innocent veil her privileged upbringing afforded her. She’s the FNG: fucking new girl, and quickly makes friends with Barb, a Black woman (another veil-remover) and Ethel, from the farm life of America. Those two are such rich, strong characters, and help, along with the war itself, to maturate Frankie, to where by 22, she feels ancient and calls additional FNGs “kids.” (But she helps them, like she was helped.)

Frankie first, wanted to follow her brother into Vietnam. He died before she even was deployed. That was the first knock against her innocence. But like any child, she also wanted to make her parents, particularly her father, proud of her. After all, he venerated military service, despite not serving himself, christening a wall in his office the “hero’s wall,” with pictures of everyone in the family who served. But when it came to Frankie’s service, he was aghast and against it. Like his wife and Frankie’s mother, he expected Frankie to follow in the footsteps of her upbringing in the 1950s: marriage and motherhood. Instead, Frankie was awash in rocket fire, mass casualty events, and the reality of the war most Americans knew nothing about — deliberately, as the United States government didn’t want people to know how bad it was going, and that the U.S. was losing and losing so many men in the process.

Speaking of men, naturally, the men around Frankie in Vietnam hit on her because she was a woman in Vietnam, a shining light in the throes of hell. Before dying, or as the wounded, being shipped off to somewhere else for recovery, men would take pictures with her because … she was a woman. Jamie was the first one, but he was married. Still harboring some of her “good girl” upbringing, and basic morals, Frankie resisted his charm offensive. Part of her wishes she’d given into it and told him she loved him. Then, he seemingly died. Next was the aforementioned Rye, aviator glasses and all, also married, who then said he broke off the engagement for Frankie, precipitating a torrid love affair. Although, I didn’t think it was love, but rather lust born of war. Hannah tells us they didn’t have much to talk about when they weren’t making love. That’s a red flag, folks! Later, back home after serving an additional tour in Vietnam out of duty to save more men’s lives, Frankie learns from Rye’s father that he also died.

Before I get too far, I don’t want to brush over Frankie’s return home. In a book that went into great detail to demonstrate how hellish the Vietnam War was for a nurse like Frankie, and the long hours trying to save lives, holding the hands of the dying soldiers, having a Napalmed baby die in her arms, and just the visceral feeling of Vietnam, some of the most intense scenes from the book were actually back stateside, like when Frankie learns her father told the rich, elite community that she was in Florence, not Vietnam. She certainly isn’t celebrated and honored on his “hero’s wall.” They were ashamed of her. In addition, she kept running into people telling her women didn’t serve in Vietnam, including Veterans Affairs itself. One scene I did mildly groan at, and which gets brought back up a few times in the book, is that upon returning, Frankie was spat on by anti-war demonstrators, who also called her a baby-killer. From everything I’ve seen, the claim that Vietnam soldiers were spit on when returning to the U.S. is a myth. For how seemingly well-researched, well-realized, and especially well-lived in the Vietnam War scenes were, that Hannah kept going back to such wildly disputed imagery is my only mark against what otherwise was a great book.

Nonetheless, grief-stricken at losing Rye, Frankie falls into depression and alcoholism, as well as continuing to deal with undiagnosed PTSD (and of course, it wasn’t even officially a “thing” yet, anyhow) until in perhaps my favorite moment of the book, her best friends, Barb and Ethel, show up to save her yet again. I had tears at their arrival! Through their help, Frankie is on the precipice of marrying another man, Hank, while also pregnant with his child, when she loses the child. This is the tide coming in for her again: Agent Orange likely cause her miscarriage. She breaks it off with Hank, because she also learns that Rye is alive. He, like many other men who served in Vietnam, was declared dead, but was actually a POW, or prisoner of war. He returns to the U.S. and instead of greeting her upon coming off the plane, he greets his wife and child. He never broke off the engagement; he lied.

I’m skipping over some of the narrative just because, like I said, it was a tour-de-force of putting Frankie through the wringer of war and its aftermath, but Part Two of the book also deals with how Barb, who then inspires Frankie, protest the war from the point-of-view of veterans, and help bring the reality of the war to Americans for the first time. Later, Frankie also helps with the POW/MIA movement. But even within that movement, they are often dismissed as women, and Barb as a Black woman in particular.

Frankie’s mom also tries to help Frankie by giving her “Mother’s Little Helpers,” aka Valium, and instead, gets Frankie hooked (in addition to her still raging alcoholism and PTSD). Frankie makes the morally wrong choice she abstained from while in Vietnam, and has an affair with Rye, who promises to break it off with his wife (a wife he admitted help him get through the hell of being a prisoner-of-war; he’s a POS). Instead, he not only stays with his wife, but has another child with her. Frankie is distraught and her spiral continues, including showing up to work in the OR high, drunk driving and nearly killing a man on a bike, which itself was likely a suicide attempt, and then an actual suicide attempt by making the metaphorical literal by wading into the tide of the Pacific Ocean.

Life is a flat circle, and she ends up with Hank (one of the best characters in the book next to Barb, Ethel, and Frankie, of course) again, albeit in a doctor-patient and friendship capacity at a psychiatric ward and Hank’s alcoholism and drug addiction rehabilitation facility. See, while I was frustrated with Frankie’s dad because of how he treated her service in Vietnam, he did love her in his way, because he saved her life, pulling her from the Pacific Ocean, and getting her help. (Also, thanks to their privilege, essentially shielding her from consequences for the DUI.) Finally, talking about what people, including her own parents, wanted her to forget about, leads Frankie to getting better, eventually moving to a secluded farm in Montana, and helping other women who served in Vietnam get better.

Again, flat circle, where by the 1980s, Frankie attends the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C., where it turns out Jamie is still alive. From a war propagandized as patriotic and one of duty, to disgraced and brushed under the rug, to venerated for their service. From Frankie’s innocence to marred. Broken by the war to healed on the homefront. Frankie experienced it all. She even reconciled with her father, who finally recognized and acknowledged Frankie. In the end, all Frankie wanted was to be seen for who she was and what she did. By her father. Her community. Her country.

Something I hope eventually accompanies this book, or a studious reader puts together, is the soundtrack to the book, because Hannah drops in various popular songs that defined the era in the 1960s, including reflecting the anti-war sentiment, and it made me want to listen to them! The one I’m listening to now as I finish this review is Percy Sledge’s “When A Man Loves A Woman.” Of course, that’s not a quintessential war song, but it was mentioned!

Hannah has captured the essence of the toil war places upon those who served, their families, and importantly, how the war follows the warriors back home and long after hostilities have ended. And yes, that women served in the Vietnam War, and saved many, many lives. Her latest is a must-read, enthralling book. Like Frankie during her service, after reading, you may have trouble washing off the red dust of Vietnam.