Spoilers!

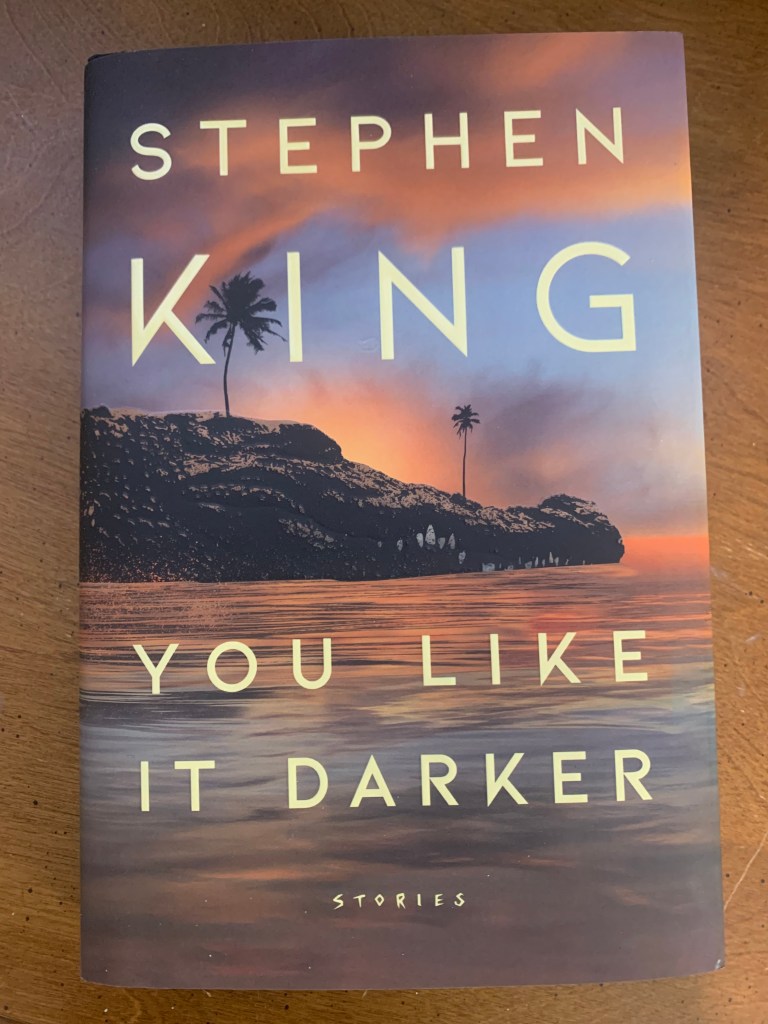

If onlies are also rattlesnakes. They are full of poison. Forget a grand unifying theory of the universe; humans are selfish and we want a grand unifying theory of ourselves. Why me? Why this? Why now? And those questions often only get more salient the older we get, when the road to the end narrows. Stephen King is a master of introspection, while still bringing the horror and his trademark zany humor, in his latest short story collection, 2024’s You Like It Darker.

In You Like It Darker, King brings forth all of his mastery for 12 stories, with two (“The Fifth Step” and “Red Screen”) less than 10 pages, and the longest (“Danny Coughlin’s Bad Dream”) around 150 pages. The overarching themes prevalent in each story, whether they’re filled with aliens, precognition, deadly alligators, ghosts, and curmudgeonly old men deep in their retirement years, concern the aforementioned “why me?” whether it be good fortune, like in “Two Talented Bastids,” which kicks the collection off, or mistaken identity in “Finn.” King’s characters may not “like” it darker, but they get it darker, even when things seem to be going their way initially, like in the unforgettable final story, “The Answer Man,” with Phil.

But King is decidedly not the Answer Man. There are no good answers as to why any one person, including King, have good fortune and others do not. Why others, like Danny in “Danny Coughlin’s Bad Dream,” are nearly railroaded and killed as a would-be-murderer, or Harold has the unfortunate timing of sitting on the same Central Park bench as Jack, an ice pick serial killer in “The Fifth Step.” Even Vic, the father in Cujo, who has the misfortune of losing his son to Cujo and then his wife, Donna, to divorce, has the fortunate of finding her years later, remarrying, having 10 solid years with her, and then losing her to cancer. Topsy-turvy is the tapestry of life. That’s the reality we’ve been dealt, whether that reality is as frighteningly real as the protective alligator in Laurie, the heebie-jeebie rattlesnakes in Rattlesnakes, the black tendrils in The Dreamers, or the alien-humanoids in Red Screen. This is our one (maybe?) beautiful life, whatever fold of reality it happens to be on from its origami-like machinations.

I also think King, who will be 77 later this year, is preoccupied with retirement, aging, and mortality. Obviously. As I mentioned in my review of 2023’s Holly, you could read that as a story built on the fear of aging and dying and the joys, depending on the characters. With You Like It Darker, many of King’s protagonists, including the bad-ass grandpa in “On Slide Inn Road,” are purposefully old and retired. The most meta story in this regard, and one which also reflects another persistent King theme — the process around writing and creativity — is Two Talented Bastids, which concerns an aging author, near death, who, along with his painter best friend, became extraordinarily rich and famous from their art. Both from a podunk Maine town, a national reporter wants to know why and how these particular two men made it. Which is the same preoccupation Constant Readers, like myself, have with Stephen King. Why and how? All of this? His ideas, his writing, his prolificness, his success. Why him? Well, at least in Two Talented Bastids, the answer is benevolent and grateful aliens.

King’s America, a country he loves and has painstakingly written about through small towns and journeys across the country in the course of his work, including here, is a country besieged by the aftermath of war on the homefront in areas (primarily with Bill in “The Dreamers”), COVID in multiple stories, and as evidenced by the wistfulness around why some achieve the American dream and others don’t, a certain melancholy about it all. Melancholy is a kind of darkness, and we like it darker. In King’s America, even bad turbulence has explanations around it, or rather, it could be worse, if not for the turbulence experts, like Craig Dixon, in, “The Turbulence Expert.” That itself is perhaps the answer King arrives at, if he does have answer to the why of anything: it could be worse, or others have it worse. That’s what Phil comes to realize in “The Answer Man,” at least. He gains all he ever dreamed about, but also loses his son to cancer and his wife to alcoholism and drunk driving. Then, he helps sue a corporation on behalf of a badly burned housewife who lost her husband and five children to faulty electrical wiring. Some have it worse. Some experience it darker.

And in King’s America, men aren’t John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. They’re just regular men, who coward out when the goin’ gets tough, or when a gun shows up, so, no judgement here. Frank in “On Slide Inn Road,” and Edgar Ball in “Danny Coughlin’s Bad Dream” both freeze when a gun comes into a play and they could theoretically help save someone(s). To be fair, at least Ball helped Danny in other ways. Frank was a “bastid.” That’s perhaps yet another answer King proffers (I know I said he didn’t have any, but if I’m reaching!) about the “why” of everything: we’re all just regular people, and some make it one way and other don’t. Or aliens. Yup, aliens.

If I had to rank the stories, which is impossible, I think I’d go like this (and again, I could go another way another day):

- “The Answer Man”

- “Danny Coughlin’s Bad Dream”

- “On Slide Inn Road”

- “Laurie”

- “The Dreamers”

- “Two Talented Bastids”

- “The Turbulence Expert”

- “Finn”

- “Rattlesnakes”

- “Willie the Weirdo”

- “Red Screen”

- “The Fifth Step”

Nobody writes like King, which is what makes King such a joy to read, even when we go into dark places with ghostly strollers, children being devoured by rattlesnakes, nagging alien wives, a lunatic number-counting detective, and a serial killer exercising his alcoholism through serial killing. King doesn’t know why we like it and doesn’t know how he does it, for that matter, but we both know we’ll meet here again the next time, if we’re lucky.