Spoilers!

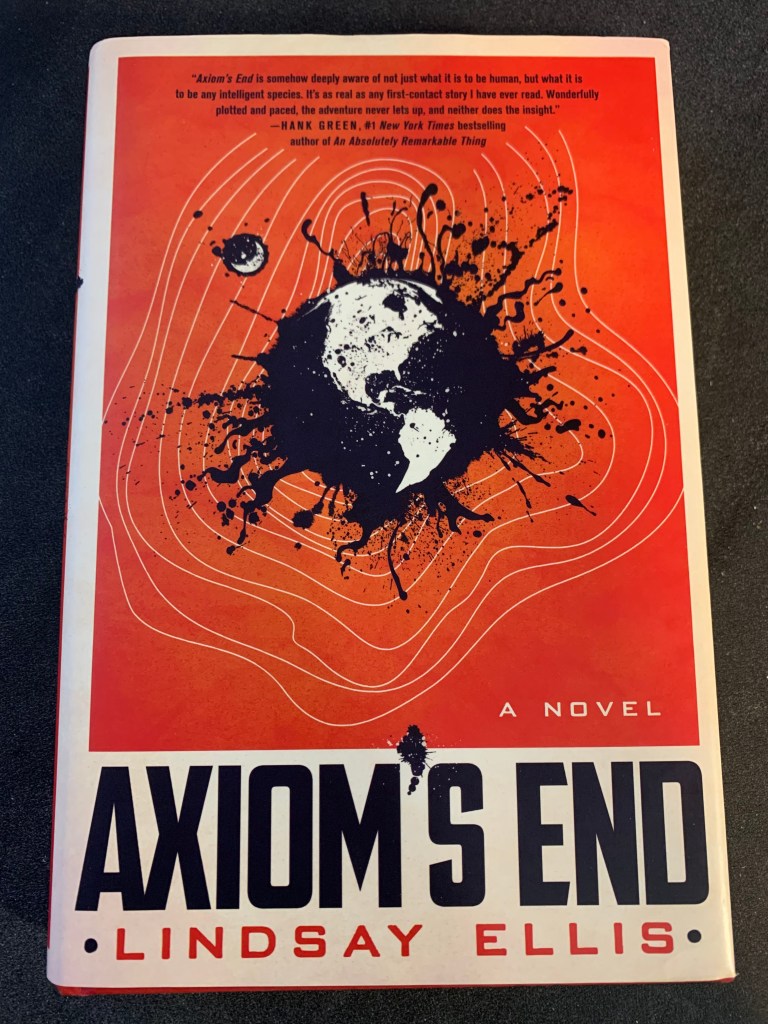

Perhaps the most alarming scenario I can imagine — while equally brilliant and marvelous — is meeting another intelligent being, particularly if that being is more powerful and intelligent than humans are. From a hierarchical standpoint, a natural order, if you will, to encounter something that necessarily accompanies or knocks humans off the top of the food chain is a scary thought! An existential-level interaction, whether that being intends us harm or not. Even if such a being or beings didn’t intend to harm us, the very concept of meeting such a being is existential on a philosophical level for humans and our understanding of our place in the cosmos. All of this is to say, Lindsay Ellis’ debut 2020 science fiction book, Axiom’s End, explores this dynamic with aplomb, humor, and the proper amount of awe.

Axiom’s End is set in 2007, a few years after 9/11 still within the George W. Bush presidency, and at the height of concerns over surveillance and government secrecy with a corresponding whistleblower claiming “truth is a human right” and leaking said government secrets. Why not throw some aliens into the dynamic? People assume our government is concealing aliens, anyhow, why shouldn’t Ellis play on that fear, as scores of authors, filmmakers, and so forth have as well? Her take on it is reminiscent of Eric Heisserer’s 2016 screenplay, Arrival, adapted from Ted Chiang’s 1998 short story, “Story of Your Life.” That is, like that story, our main character, Cora, is a linguist. Because language and communicating with other people is one of the fundamentally most intriguing aspects of, well, being human, so, naturally, it’s an intriguing prospect of intergalactic communication.

Cora also happens to be the oldest child of Nils, the aforementioned whistleblower, who is a terrible father, but a righteous whistleblower of the government’s coverup of the Fremda group, aliens who landed 40 years ago in America. In this timeline, Bush resigns the presidency after being caught by Nils lying about First Contact with aliens. But where Cora comes in is that reams of researchers and other linguists, like her aunt on her father’s side, Luciana, have not been able to communicate with the Fremda group, who the government considers refugees from another part of the universe. Another member of the Fremda group, who received their distress call, who Cora takes to calling Ampersand, arrives on earth, and tries to use Cora to locate the Fremda group. Thus begins their book-long relationship, where Cora acts as his interpreter, and he’s able to communicate with her thanks to both an advanced English language algorithm device and because his species, the Superorganism, visited earth nearly a 1,000 years previously and experimented on humans to learn the language.

That is also the fascinating aspect of intergalactic travel, i.e., the time problem, because the Superorganism’s understanding of humans, and by extension, Ampersand’s, is that we are flesh-eating monsters. We are the aliens! Hence his reticence to converse with Cora at first, and certainly, the Fremda group’s with the researchers and linguists. But how is it that this species exists, along with another species known as transients who are a sister species to the Superorganism? In other words, what about the Great Filter problem? At some point along advancement, the thinking goes, intelligent life dies out before it can contact other intelligent life. Ampersand explains to Cora that the Superorganism’s axiom was that planets that support life are so competitive and dangerous that advanced civilizations can never evolve, and advancements such as theirs are unlikely to the point of impossibility. Essentially, their axiom is our Great Filter thesis. As Ampersand notes, though, this is also a useful theory going back to my scary consideration at the top: it still centers us, or in this case, them, at the top of even hypothetical hierarchies. Ampersand’s answer to Cora, and the overcoming of the Great Filter problem is that we are just as interesting a discovery to them as we would find them to be. Which makes sense! We’re also intelligent! The existence of humans is the “axiom’s end,” thus, the greatest discovery of all time, and also, a unique threat to the presume hypothetical hierarchy. As such, if the Superorganism realizes we have advanced and will continue to advance, then we suddenly pose a threat to the Superorganism, and like it has done to a planet of transients, it will destroy us. Sterilize us out of existence. Interestingly, in a parallel to the ongoing Iraq War in this timeline of the book, the Superorganism would perpetrate a preemptive strike against humanity. Cora hopes Ampersand will stop that from happening. She’s also frustrated with one of the government researchers who isn’t worried about it because it won’t happen in his lifetime, i.e., a parallel to the climate change issue now.

Naturally, Ellis’ story isn’t merely about First Contact; the stakes are higher because of the Superorganism’s machinations and hierarchical caste system. That is, when a member of the Fremda group sent a distress signal to Ampersand, the signal was also heard by Obelus, a higher up being in their system, who seeks to finish what the Superorganism started on their structure (not a planet, but a structure): extermination of the inferior genes of the Fremda group. In that way, Cora, and the military and CIA she’s working with, are caught up in the middle between the seemingly, or relatively, benign Fremda group of aliens, who are considered post-natural quasi-mechanical beings, and the avatar of the Superorganism, Obelus, who, if he so chose to, could exterminate all of humanity in a matter of days.

I love when I’m reading a book and its influence seems clear to me, and then I find that inkling validated by the Author’s Acknowledgements. In Ellis’ case, reading that dynamic between Cora, Ampersand, and Obelus reminded me of the Transformers and Optimus Prime. Then Ellis said she was influenced by the Transformers in her Acknowledgements! But I digress. Good science fiction taps into the prevailing notion of our humanness. Because, again, from an alien’s perspective, especially based on a lag of a nearly a millennium, we can seem like flesh-eating savages. And up against aliens like Ampersand himself or Obelus, certainly, we can seem so … insignificant. Easy to eradicate, as it were. But there is an intangible quality to our humanness — kindness is the word Ellis puts to it — that resonates even beyond language and cultural barriers and intergalactic barriers. Cora showed Ampersand kindness. That mattered and made a difference. She represented the best of humanity and in so doing, she may have, at least temporarily, forestalled the existential threat to humanity’s continued existence.

Ellis’ book was a delight to read because, as you can see, it made me think a lot about existential questions, but it was also a funny and fun book to read. At times, Cora and Ampersand felt like a buddy cop movie, except one was an alien. I laughed out loud. I thought. I read anxiously hoping neither Cora nor Ampersand would die (they don’t!). If I had any critique, I’m not sure Ellis fleshed out the issue with government secrecy and First Contact as much as it could have been fleshed out from the public’s point-of-view. It also seemed like the public, and Nils, seemed more upset about the cover-up, which is bad, than what was being covered up! Aliens! In our midst!

But it also looks like there are two more books that follow the events of Axiom’s End (and maybe even four total after this one!), so perhaps that aspect will be fleshed out more. You can bet I’m going to buy and read them.