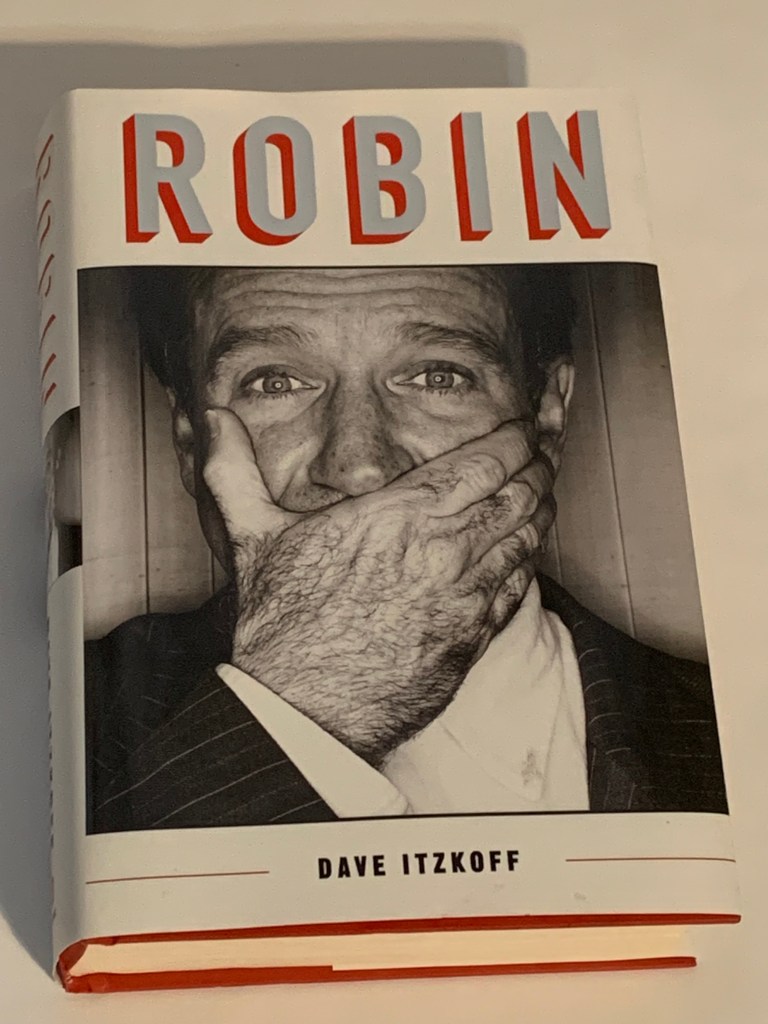

Shakespeare and the street. Somber and schtick. Self-effacing and self-deprecating. Robin Williams. The world knew him and nobody knew him. Known as manically hilarious, the man of many voices, and at least to me, my first mental image is of him in the green wool vest with checks from 1997’s Good Will Hunting. Yes, that’s my all-time favorite film — a great deal of that because of Robin — but I’ve always held to the sensibility that sometimes it is our comedians who are best able to tap into dramatic roles. Sure, due to the unexpected juxtaposition, but also because comedians often are already tapping into the human condition for laughs; it’s not much of a lift to reorient that excavating for dramatic purposes. And I’m not sure anyone of a modern, public persona tapped into the human condition quite like Robin Williams. The former culture reporter at The New York Times, Dave Itzkoff, in his 2018 book, Robin, details how complicated and in some ways, how simple, Robin was. As mentioned, as public as he was and as giving as he was to others, Itzkoff details how even those closest to Robin never felt like they quite knew him. In a way, he was always performing; there was no “off” button. But also, like the manifestation of the basest of all of our insecurities, Robin had a deep yearning and need to be liked, validated, and recognized. Which is perhaps why he always felt the need to be so “on” and giving toward others, perhaps to his detrimental professionally and personally. Complex and simple. The human condition, in other words.

Without qualification, Robin is one of the best biographies I’ve read and among my favorite nonfiction reads in years. Itzkoff elevated a biography of someone I was already deeply interested in into a can’t-put-down read, and indeed, one of those quintessential books I’m thinking about when I’m not able to read it. At 440 pages (hardcover, not counting the notes and index), Robin felt breezy, which is the best compliment I can give someone’s prose, and I easily could have read more. Itzkoff intersperses the descriptions of what’s currently happening in Robin’s life — whether his upbringing, his missteps through college, personal relationships, TV and film roles, his relationships to his children and so on — with quotes and observations from a variety of people in Robin’s life, such as close friend and fellow comedian, Billy Crystal, David Letterman, Robin’s son, Zak, and Robin himself, who Itzkoff spent time with in 2009. These varied quotes and observations from Robin’s closest family and friends throughout his life help to paint the complex characterization of Robin the superhuman-like comedic force of nature and celebrity and Robin the man, with all the fallibilities and shortcomings of a man. Indeed, Itzkoff does not flinch away from Robin’s alcoholism, drug abuse, infedilities, and acknowledgement that Robin could be handsy (for lack of a better word) with women in the 1970s and 1980s in a way that wouldn’t be seen as “cute” and “that’s just Robin” today. But also, Itzkoff’s rendering of Robin reminds me some of his maligned performance of the titular character Jack in the 1997 film, Jack (which I remember fondly, for what it’s worth!): A grown man on the outside with a child-like brain and outlook. Again, the almost childlike needy way in which Robin, well into his 50s and after multiple Academy Award nominations and one win (for the aforementioned Good Will Hunting performance), along with box office success and amassing millions of dollars, needed affirmation. “Boss, did I do good?” It’s both sweet and sad in equal measure. Sweet in that I can relate to imposter’s syndrome and being desirous of validation, but also sad because he’s Robin freaking Williams! He wasn’t always Robin freaking Williams, though. What’s so interesting when you read a book like Itzkoff’s is how much fame and fortune is a combination of luck and talent finding the right timing and people to capitalize and catapult the talent part. And also, it’s worth saying, coming up in show business in the 1960s and 1970s was just different than today. It’s hard to imagine the way in which those who broke into the business, like Robin, slumming it in NYC at the Juilliard School, to make it happening today. Maybe I just haven’t read those stories yet!

Robin’s father was stoic and always seemed to keep Robin, and his affection and approval, at an arm’s length. It didn’t help, either, that his job at Ford and then as a banker, brought disruption to Robin’s upbringing and ability to establish roots. I don’t want to be one of those people who armchair psychoanalyzes Robin, especially given his death, but it does seem like his need for approval stems from his father. For the longest time, his father disapproved of Robin’s desire to go into show business. The long-running joke, albeit it seems true, was his father wanted him to take up welding instead. Far more practical! His mother struck me as a combination of Southern formal (her grandson remarked that she wore a miniskirt every day of her life up until death) and California hippie. Perhaps that gave Robin enough wiggle room to be … Robin. As an only child for all intents and purposes through much of his upbringing (both parents had a boy from a previous marriage but they came into Robin’s life later-ish it seemed to me), Robin had the time to explore his own imagination, test out his voices, and sponge up the comedic inspiration of the comedy giants of his time, such as Jonathan Winters. I didn’t know Robin was classically trained, which is why I presented the “Shakespeare and the streets” dichotomy earlier. Robin could quote Shakespeare as easily he could do a crude and lude joke because of his Juilliard school training and theater background. Surprising to me also, was that Robin and Christopher Reeve met at Juilliard and became close friends through to Reeve’s death in 2004. Cartoons aside, Reeve was likely the first celebrity I put on a pedestal as a hero. Initially because of him literally playing Superman and then because of the man himself. Robin and Reeve’s close relationship was touching, especially how Robin cheered up Reeve after his horse accident left him as a paraplegic in 1995.

But yes, luck and timing. Happy Days needed something to juice it up. (I had no idea Happy Days ran for 11 seasons; that means it ran for another six seasons after Fonzie jumped the shark!) So, creator Garry Marshall was asked by the studio to come up with something. His son was into space. Enter the Mork character, which went to Robin in 1978. His first real break. That then led to the Mork & Mindy sitcom, interestingly enough with Pam Dawber, who would go on to marry Mark Harmon of NCIS fame (to me, that’s how I know him!), which was Marshall BS’ing a concept to the studio, but it worked out, at least for four seasons worth.

From Mork & Mindy through to his early 1990s film roles, a common theme Itzkoff notes is how to harness, as it were, Robin’s manic comedy. Robin was chasing a film that would bring him critical and commercial success, i.e., to break through into Hollywood film-making. Robin would be lambasted by film critics if he veered from the comedy people knew from his stand-up and other ventures, like in 1990’s Awakenings (again, another film I remember fondly!), and started roasting him for continuing to pick roles that were so serious and waxing philosophical about the human condition. Even after his Academy Award nominations and the win, some critics still thought he was a great comedian, but only a passable actor. I don’t understand that. My favorite film roles of Robin’s were the serious ones and I appreciated the comedy ones when they happened, too, because obviously, he is a manic comedic genius. I mean, 1993’s Mrs. Doubtfire is an all-time film and one of those endlessly watchable ones at that.

Robin’s need to be liked seemed to express itself in workaholism: he needed to always be working because he was always chasing that need, and therefore, he often took roles he probably shouldn’t have. They became commercial and critical flops, potentially dimming his leading man bona fides. Just the way film productions and releases work, I believe Good Will Hunting and 1998’s Patch Adams were released around the same time, resulting in, as Itzkoff notes, Robin’s Hollywood high and low occurring simultaneously. What also made Itzkoff’s book so fascinating is the behind-the-scenes we get on various film productions and the relationships therein. For example, I didn’t know Steven Spielberg and Robin were so close. Another example is that Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall, Ed Harris, and Morgan Freeman were all considered for the part of Sean Maguire in Good Will Hunting. As great as all of them are, I can’t imagine any of them playing the role opposite Matt Damon’s titular character, Will, the way Robin did. It’s probably cliche at this point, but Robin just had such a damn soulfulness about him that always made those serious roles he did so good and endearing.

Until 1987’s Good Morning, Vietnam, which shockingly I haven’t seen yet, the figurative career obituaries were being written about Robin. He was becoming a “what happened to that guy” sort of entertainer. The one with promise and potential, but who couldn’t ever find the right role. Good Morning, Vietnam changed that, providing the perfect role for Robin’s zanniness and talents and an indelible line that I even hear in my head despite not having seen the movie: “Gooooood morning, Vietnam!” Robin’s voice is so identifiable on its own, much less how fun all his voices and accents can be. I’m shocked he didn’t lend his voice to animation even more, although obviously he did to great fanfare with 1992’s Aladdin, at a time when big name actors weren’t doing that.

In 2002, Robin explored his darker side in his “villain triptych,” Itzkoff calls it, starting with One Hour Photo, Death to Smoochy, and Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia. I remember my first experience with One Hour Photo: shock! Robin’s bad! And he doesn’t look like Robin! But what a great, if unexpected, performance. Again, I think there’s something comedians can tap into that make them great villains. After that, I’m not sure Robin had much of anything in the way of wide commercial appeal or critical success for the next 12 years before his death. Yes, there’s Night at the Museum, but as Itzkoff rightly notes, its success can hardly be attributed to Robin’s involvement. I do feel like people have turned 2007’s World’s Greatest Dad into a cult film, perhaps also owing to Robin’s death. Weirdly, given how much a fan of his I am, I’m one of the masses who didn’t see any of his work after his villain turns besides the first Night at the Museum. I especially had no idea he had a very short-lived sitcom on CBS in 2013 with Sarah Michelle Gellar called The Crazy Ones. Those two could have been an inspired pairing with a better premise, and as Itzkoff notes, the single-camera style (which has been fashionable for a while now) as opposed to a live studio audience for Mork & Mindy, didn’t suit Robin.

I also didn’t know that five years before his death, Robin had heart surgery, which is darkly comedic given the jokes he made with Letterman after his own heart surgery. In the last stretch of his life, Robin was dealing with severe depression — he was on antidepressants for much of his adult life — and anxiety, as well as, most significantly, what was diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease, but was actually later thought to be Lewy bodies dementia.

Robin’s drinking and substance problems were the hardest to read about next to his unrelenting desire to be liked and loved. He enjoyed sobriety for decades before falling off in the early 2000s, rupturing his second marriage with Marsha Garces, who was such a positive force in his life professionally and personally, as his minder and organizer. When you read about someone with an addiction, it’s always difficult to read when they fall off the wagon because you don’t want that to happen, obviously. A few years before his death, he then married graphic designer Susan Schneider, who was a rather divisive figure in the book as told through the quotes and observations of Robin’s friends and family. She wasn’t Marsha, with careful minding of Robin, and she kept Robin’s three children at arm’s length. The 2000s in general were a difficult time for Robin. He lost his mother, one of his half-brothers, his close friends, Reeve and Richard Pryor, fell off the wagon, lost his marriage to Marsha, and then of course, the heart issue and (mis)diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. The latter was seen by his closest friends as likely a big blow to him: this man known for his manic personality and body comedy, and his photogenic-like memory and rapid-fire wit is going to be slowly diminished until his death by Parkinson’s. That more than depression or something else is what caused him to take his own life, those close friends surmised. We don’t know because he didn’t leave a letter (which isn’t unusual) or otherwise give any clear red flags that he was thinking of ending things.

I remember being flabbergasted when I saw the news that Robin was dead and how he died. But I also think there’s something in the zeitgeist when it comes to comedians — or anyone in the public eye who is deemed unabashedly good (Anthony Bourdain comes to mind as another example here) — that to be as genius as they are, as observant of the human condition as they are, as giving to others in that way as they are, there also must be a deep-seated sadness and darkness behind it at all rendering the outcome not actually surprising. I don’t like the idea that Robin (or Bourdain) were preordained to end their lives, but that sensibility is salient all the same. Regardless, there are no easy answers when it comes to suicide. More than anything, it engenders a deep sadness from family and friends (and the public because we feel like he’s “ours”) that we wish he could have known how loved he was and how much he uplifted others throughout his life.

Robin, you were loved by me, who took great joy from your work and found a great deal of resonance with your more serious offerings. On a regular basis, I think about your monologue to Will about remembering the “little things” about your wife, who had passed. Or the bench moment with Will. Or the hug. That’s all you.

If you, too, loved Robin, then Robin is an indispensible look into the seemingly superhuman comedian and actor and particularly to the very fallible, but endearing, man.