Spoilers.

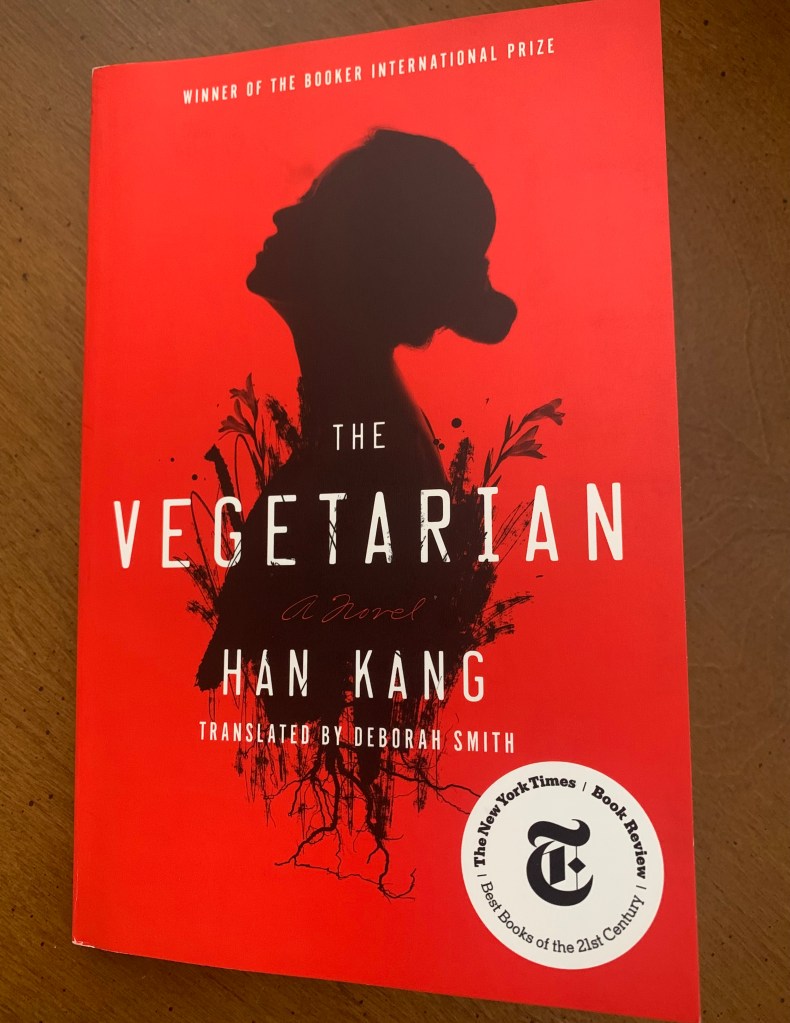

Depression is that insatiable hunger within, hollowing out your being, making you feel inhospitable to the world. You become the antithesis of living. The hunger often begins before we understand its carnal pangs and can put words to it. Maturating is to metastasize it. Family and friends often are left flatfooted before its ravages, not recognizing the person its overtaken anymore. That is, if death hasn’t claimed the person afflicted yet. For unlike a parasite who needs its host to live, depression seeks such an end. All of what I’ve described – indeed, have experienced short of death – is conveyed in Han Kang’s 2007 book (translated into English by Deborah Smith in 2015), The Vegetarian. Kang’s writing and descriptions of depression’s malaise and torment made for a hypnotic reading, evoking the very trance-like state her characters were in.

Set in Seoul, Yeong-hye decides to stop eating meat after having a gory dream. This disturbs her husband, Mr. Cheong, who expects his intentionally “unremarkable” wife to be dutiful and obey him. He also rapes her repeatedly when he deigns to have pleasure. So, the idea that she’s chosen to not eat meat, and to not even have meat in the house for him, is scandalous. But it doesn’t stop there. Over time, Yeong-hye largely stops eating altogether, becomes thinner and thinner (down to around 60 pounds by the end of the novel), and also unashamedly exposes her nipples and/or breasts in public. Mr. Cheong gets her family involved. Her mother, father, brother, sister, and the sister’s husband, all come over. The father, a stern, which is to say abusive, father, slaps Yeong-hye across the face and forces her to eat meat. She’s able to break away and uses a fruit knife to slice her wrist. Throughout this section, Mr. Cheong references what I said earlier: not recognizing who Yeong-hye. She’s become a stranger. No, not because of her physical deterioration, but because of what her mental illness has done to her.

The next section of the book is told from the perspective of Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law, who has become infatuated with her, particularly her blue flower petal-like Mongolian birthmark on her butt. (Mr. Cheong was also infatuated with his sister-in-law.) As a starving video artist, at least mentally, the brother-in-law is inspired by her Mongolian mark to make a video project with her as the centerpiece. He paints her nude body with flowers, all while filming. Then, he convinces another male artist to have his body painted with flowers and tries to cajole the artist to have sex with Yeong-hye. Flowers on flowers. He rebuffs the effort, but Yeong-hye is seemingly titillated by the flowers. This is the next evolution of her becoming plant-like, from eating only plants to an infatuation with the consuming aesthetic of flowers. Yeong-hye rejects the brother-in-law’s sexual advance thereafter because he’s not covered in flowers. So, he gets a former lover to paint him in flowers and then he has sex with his sister-in-law, also on film, before being discovered by his wife. The wife calls the paramedics to take Yeong-hye to a psychiatric institute and blames the husband for taking advantage of his sick sister. The husband wants to kill himself, but is unable to leap over the balcony and is prevented by the paramedics, anyhow.

In-hye, Yeong-hye’s sister, narrates the final section of the book, “Flaming Trees,” a time jump of about a year, with Yeong-hye receiving regular psychiatric treatment. However, Yeong-hye seems to be deteriorating and on the precipice of death, refusing to eat and incapable of being force-fed. She’s also disappeared to be with the trees nearby and stands on her head like a tree. The full evolution to plant-like is complete. We also learn that In-hye nearly attempted to kill herself years before, but only the thought of her son kept her from doing so. As the older sister, she always thought she was being dutiful and hardworking. Instead, especially back in the familial context with her abusive father and Yeong-hye, she realized she was engaging in survival tactics. With her husband and her job, In-hye becomes essentially a functional depressive. She reflects, “Her life was no more than a ghostly pageant of exhausted endurance, no more real than a television drama. Death, who now stood by her side, was as familiar to her as a family member, missing for a long time but now returned.” In-hye and her husband, then, share that they are unable to take that next step into Death’s embrace. By contrast, when In-hye is interrogating her sister asking her if she wants to die, Yeong-hye replies, “Why, is it such a bad thing to die?”

Kang’s book has taken root in me because of how seductively her prose elucidated the all-encompassing, reality-warping effect of depression and mental illness and how it leaves families completely bereft as to a course of action (for what it’s worth, Yeong-hye was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and schizophrenia). The Vegetarian will not be for everyone, but for those who have been under the canopy of mental illness, or known someone who has, Kang’s book will surely resonate with them as it has me. I’d be derelict if I didn’t mention this is my interpretation of the book. Nor is it my only interpretation, as Kang has much to say about Korean patriarchal society and the role of women, for example. Someone else may interpret the book in different ways. That’s just another credit to the power of Kang’s writing and story.