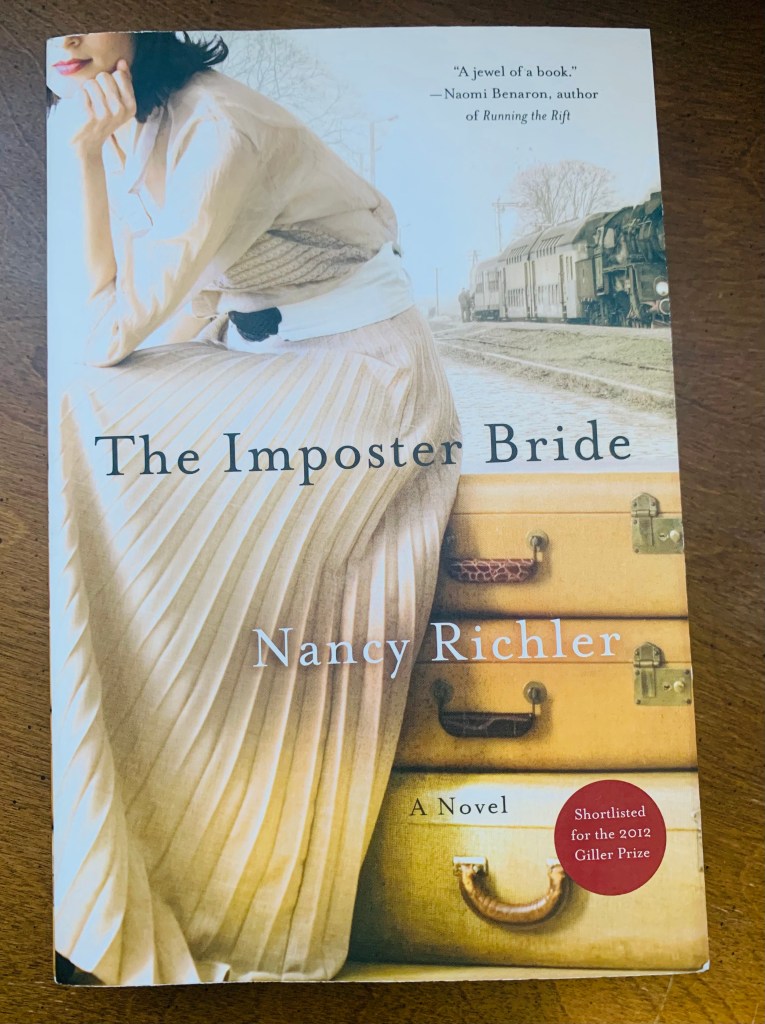

Though the war may have ended, an inferno of a kind was at their backs, chaos still permeated the ruins of the landscape and indeed, the ruins of their origins, and thus, their destiny. To be human is to be curious about our origins, which informs our destiny — with an unknown origin, what then is our destiny? Nancy Richler poignantly unearths the roots of one family’s origins in the aftermath of WWII in her 2012 novel, The Imposter Bride. About half-way through this book about a Jewish woman who assumes the identity of a dead Jewish woman to ensure passage into Canada, I teared up upon the realization that everyone who survived the Holocaust was, in some measure, an imposter when everyone is looking for their dead. To paraphrase the dead Jewish woman’s diary, to live is to be a walking graveyard, the dead buried within your skin. That’s why those who survived look at your own survival and wondered if you were their relative. Grief masquerading as hope. It’s a heartbreaking reality, an unfathomable survivor’s guilt, and in the case of Richler’s book, a survivor’s guilt that drives our titular “imposter” to abandon her child three months after birth. An act which reverberates throughout the family and most acutely upon the abandoned child, leading to a 58-year quest to learn about her mother, her origins, and her destiny.

Lily, the name of the dead Jewish woman whose identity as been assumed by this other Jewish woman, comes to Montreal to marry Sol and start life anew, but Sol calls off the marriage upon seeing her depart from the train. His brother, Nathan, steps in and decides to marry her. Lily accepts it, saying, she will be grateful. “She, who had held all of life and death between her two hands before dying and washing up into this pale afterlife of her own existence.” That reflection, considered on page three of the book, portended what Lily would go on to do with Ruthie, her daughter.

I’ve always been fascinated by what that period — immediately after WWII and the first few years thereafter — must have been like, trying to rebuild and continue living after surviving a global war that claimed millions of lives and a Holocaust that claimed millions more. But as Richler reminds us, “people come along.” “It’s the nature of our species to come along …” And so it was for those still standing after the war, those still alive through the horrors of the Holocaust, and those like our main character, Lily. She was adrift in a foreign land sunk by a deep depression and the aforementioned survivor’s guilt at what she had done to even get to such a place. The others around her, Ida, the real Lily’s cousin, and Belle, the mother of Nathan and Sol, also Jewish, have “come along” despite the events of WWII and indeed, their own personal trauma (Ida’s husband left her and their daughter, Elka, to remarry and have children elsewhere; and Belle’s husband lost his vigor after the war and then was tragically killed in a vehicle accident). But Lily didn’t want to come along. She wanted to go a long way away from it all. And maybe she also worried that Ida was “on to her” imposter status.

Ruthie, though, would grow up wondering about her mother, and even receiving random rocks in the mail from places her mother had visited. She hoped Lily’s diary held the answers, but it was written in Yiddish, a language she didn’t speak. Ida, Belle, and Nathan refused to read it for her for the longest time. But unfortunately for Ruthie, it held no answers except of Lily’s own experiences during the Holocaust. Still, Ida would eventually reveal all, with Belle filling in the final gaps in knowledge, so that many years later, once Ruthie was herself married and had three children, would travel to “Lily’s” home. Ruthie’s mother remarried and had a son within six years of abandoning her. Ruthie isn’t too ruffled by all of that, however. I think she just wanted to know her mother was alive and healthy. There would never be a sufficient answer or rationale to hear from her mother about why she left when Ruthie was only three months old. Correspondingly, Richler doesn’t provide us one, only the mother apologizing and trying to explain how adrift she felt upon coming to Montreal.

Richler’s book is not an easy read. Like Lily analogizes about her experience, it’s akin to wading through the mud of grief, abandonment, loss, and the terrible claustrophobia of not knowing. In Richler’s hands, the words are lovely and beautiful, incisively getting at the core of what makes us … us. Untethered, it’s hard to center ourselves and to understand ourselves. We will always long for the tether, if it’s not there. Even if it means walking as a graveyard, or through the graveyard of the past, to uncover it.

One thought