Spoilers!

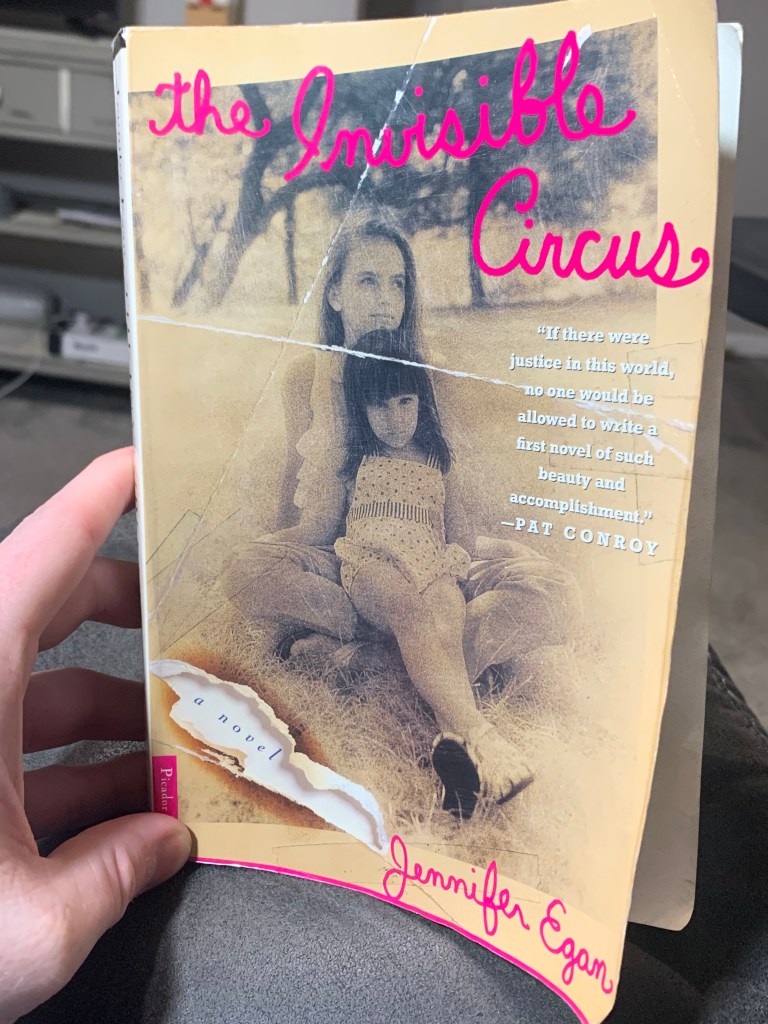

To borrow from Camus, life is absurdity and the beauty in life — the meaning inasmuch as it can be found — is to struggle against the absurdity, to defy it. Or in another sense, life is a circus, often an invisible circus, a traveling carnival of oddities and absurdities, however long the journey lasts. Jennifer Egan creates a hypnotic, hallucinatory “traveling carnival of absurdity” in her debut book, 1994’s The Invisible Circus.

Phoebe’s older sister, Faith, who is a child of the 1960s, killed herself in Italy by leaping to her death. She was traveling through Europe, sending jovial postcards home that belied the anarchism and chaos she was actually partaking in. Years later in 1978, Phoebe, now the same age Faith was when she killed herself, 18, absconds from her home in California to follow the same path Faith took through Europe using the postcards, with the ultimate destination being Italy, and specifically, the site of her sister’s suicide. Phoebe and her brother, Barry, along with their mother, are dealing with the pall over their family not only of Faith’s suicide, but of their father’s/husband’s death as well from cancer. Phoebe mostly has been the one in a sort of stasis — unable to conjure up a future with herself in it, while the mother not only seems to be dating someone new, but has plans to sell the family home. Barry is on the cutting edge of computers and a self-made millionaire.

In this way, Egan’s concept of the “invisible circus” has three metaphorical lens through which to examine the themes of the book. The first is that of the 1960s as a “circus-like” milieu. It came in, set up, and before the mid-1970s everything that defined the 1960s was quite literally dead or culturally dead. The circus moved on. One character later talks about how if something last long enough, it becomes its opposite in the end. That’s perhaps an apt way of thinking about the 1960s and the ways in which teens and adults of that era abandoned what made them ’60s kids in the first place. Second, grief is absolutely an “invisible circus.” You could be walking next to someone on the street and have no idea the internal turmoil their experiencing brought upon by grief, but that doesn’t make it any less real. Phoebe most pointedly is dealing with the weightiness of grief, the invisible circus playing havoc on her conception of self and her ability to think beyond the past. Third, which creates a throughline between Faith’s exploits in Europe and Phoebe’s travail through the continent, is that they move about like a traveling circus, from London to Belgium to France to Germany to Italy. Each place seems magical until it loses luster and they move on, almost, and sometimes quite literally, as if chasing an insatiable high.

Ultimately, what Phoebe seeks through her grief is that which anyone faced with Faith’s particular manner of death — suicide — seeks: closure. Those “left behind,” as it were, need to understand the why of it. And Phoebe, as the younger sister, sees Faith as larger-than-life, headstrong, afraid of nothing (often as spurred on by the father, much to the mother’s chagrin), and therefore, is unable to imagine that her sister would take her life. So, in some sense, it’s almost as if she’s expecting to find Faith in Italy, still alive, still romping through the world doing it her way. Egan so achingly creates a palpable sense of Phoebe’s need for closure that I started feeling the climax coming, as she built to the destination in Italy. What were we, the reader, going to find alongside Phoebe in Italy? Before she reaches Italy, though, Phoebe encounters Wolf, Faith’s complicated boyfriend, who traveled with her to Europe, in Munich. Wolf is somewhat of an unreliable narrator owing to his reticence to share what really happened to Faith. However, with enough cajoling from Phoebe, including a sexual affair (Wolf is engaged to be married, and also, it should be noted, knew Phoebe when she was just a child, so it’s a bit icky), Wolf reveals what Faith was actually up to in Europe. Essentially, Faith fell in with the left-anarchist crowd of the 1960s and 1970s throughout the Western world that was setting off bombs and otherwise trying to disrupt the “fascist establishment.” Only in Faith’s situation, it went too far and a janitor was killed. Faith blamed herself for his death and subsequently killed herself. Wolf reveals for the first time that he was there when it happened.

When Phoebe goes to the site of Faith’s death, it absolves her of the “Faith pall,” if you will, that’s been present with her since she was a 10 year old girl. It does provide closure of a kind. If anything, it reinforced her own will to live and finally chart a path for her own future. Her grief is no longer all-encompassing and suffocating. She returns to America and picks up the pieces of her life, including her family life, albeit, she was rather surprised how much the world she knew kept on spinning.

In this world of absurdities, it can feel like nothing changes. We just blip from one absurdity to the next, but the overarching absurdity of it all remains. That’s what Faith and the left-anarchists were agitating, unsuccessfully, against. That’s what Phoebe, in her way, was agitating against. That’s what Phoebe’s family, in their way, were agitating against. But Wolf, of all people, provides a sage and poignant way of looking at how much the world does change and often, quite rapidly (page 222 of the paperback edition). He and Faith are at the Olympic Stadium Hitler built for the 1936 Summer Olympics smoking a blunt and getting stoned. Wolf remarks, “When you feel like nothing changes, think of that.” They were getting stoned in the place Hitler built only 33 years after he killed himself in a bunker toward the end of WWII. The circus, while very deadly and serious, moved on.

Egan’s book is impressive, especially as a debut, in its intimate scope, as she insightfully excavates feelings of grief, and is also surprising in the way it becomes a compelling coming-of-age sojourn through Europe. She’s flawed and complicated, but you will fall in love with Phoebe as I did.