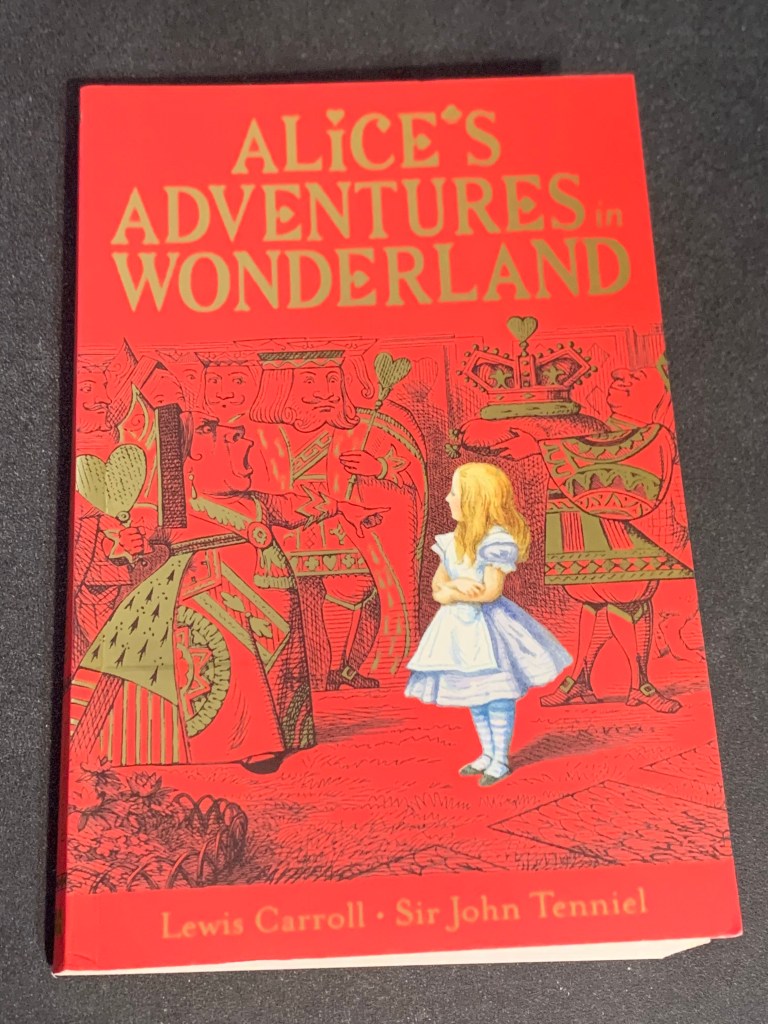

I was motivated to finally read Lewis Carroll’s 1865 classic, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by the fact of having never read something so omnipresent in Western culture, and for work purposes. I’m not even certain I’ve seen the 2010 Johnny Depp live-action adaptation in full, and I most certainly haven’t seen the Disney animated film from 1951. As such, you could say this was truly my first time down Carroll’s “rabbit hole.” What I loved about Carroll’s story, as accentuated by Sir John Tenniel’s rather (intentionally) ugly and silly drawings, was how much the book revels in the frivolity of childhood and imaginative wanderlust. And I have to remark upon doing so in 1865 (after the American Civil War ended!), when allowing children to be children was still a rather nascent concept.

Alice, rather bored with her day with her sister, stumbles through a rabbit hole after chasing the White Rabbit, who is fretting about being late, and falls for what seems like miles and miles, given how much time she has to consider her falling. That’s the other aspect of Carroll’s book that is delightful: adding a sense of the cerebral to a child’s mind! There’s a whole world in there adults even now sometimes dismiss. Once she’s at the bottom, Alice endeavors to go through a rat-sized hole to a garden, but is far too big. A bottle magically appears with the note to “drink me.” When she does, Alice shrinks to 10 inches. But upon going back to the rat-hole, she forgets the necessary golden key and is now too short to reach it atop the glass table. Then, a magic cake appears, imploring to be eaten, which causes Alice to grow substantially, with Tenniel depicting her with a giraffe-like neck. That’s when Alice exclaims her famous line, “Curiouser and curiouser!”

From there, Alice has a succession of weird and jumbled conversations with all manner of characters. One of these is the hookah-smoking Caterpillar, who basically wants to know who Alice is, and at this point, given how “queer” everything is from the day before, Alice isn’t quite sure who or what she is anymore. Down here, she keeps changing. She remarks to the Caterpillar, “Only one doesn’t like changing so often, you know.” As a child, Alice pontificates a resonant feeling! But the most poignant interaction in all the book is when Alice runs into the Cheshire Cat, who aside from the ability to teleport his temporal being, or at least its head, is not as aberrant as the other characters. Alice implores the Cheshire Cat to tell her where to go. The Cheshire Cat tells Alice it depends on where you want to go, to which Alice said she doesn’t much care. And with continued profundity, the Cheshire Cat tells Alice, then it doesn’t matter which way you go. Persistent, Alice says she just wants to get somewhere. To which the Cheshire Cat remarks, “Oh, you’re sure to do that, if only you walk long enough.” To a child’s mind, this might seem most unhelpful. After all, Alice is seeking guidance quite literally here. However, for the adult reading this, the metaphor is readily apparent: In order to get where you want to go (in life), you have to have a destination (goal and/or outcome) in mind! Beyond the poignancy, I also just love how the Cheshire Cat reminds Alice that “we’re all mad here.” Because they are! (And we all are!)

Through the rest of her journeys, Alice runs into the Hatter, who provides the unsolvable riddle, or rather, the riddle with no answer as Carroll devised it (Why is a raven like a writing-desk?), and one of my favorite characters, the Dormouse, who is prone to falling asleep and also provides the great line about there being “much of a muchness.” That’s a succinct way of describing Wonderland. Alice also runs into the Duchess and the cook with their pig baby and copious pepper, and the hilarious Queen of Hearts who (quite earnestly!) keeps calling for everyone to be beheaded: “Off with their heads!” Which leads to an amusing moment where the King and Executioner argue over if the Cheshire Cat can be executed since he’s a floating head with no body.

Alice eventually “escapes” the rabbit hole and Wonderland, as it were, by waking up next to her sister’s side, all of it having been a dream.

The moral — and there is a moral, as the Duchess reminds us, everything has a moral, if only you can find it — of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is simple enough. Mustard and flamingos flock together like birds of a feather, and watch out for their bite. In all silliness and seriousness, I think the moral of the story is the unabashed whimsy of being a child and never losing that sense of whimsy as one grows older. Unfortunately, “going down the rabbit hole” has taken on a negative connotation in the digital age, indicating someone who is being exposed to all manner of ugliness and conspiratorial thinking, the depths of which know no bounds on the internet. But in the Carroll context, to go down to the rabbit hole is to re-embrace and re-ignite that childlike wonder for the world — to see it anew in all its glorious silliness.

At least, that is my first impression and thoughts upon reading the book. What are your takeaways?