Those who can turn their trauma and grief into art and testimony enable history to not be forgotten. It is the survivors who allow the victims to receive justice inasmuch as justice is available. To think, so much of what we know and understand about the worst atrocity of the 20th century, the Holocaust, is due to survivors who experienced and witnessed unfathomable cruelty, deprivation, and violence. However, to paraphrase one Holocaust survivor, she said about her experience it wasn’t the inhumanity of her tormentors that stood out to her, but rather the humanity of the victims. Similarly, what astounds me about the Holocaust is not so much the depth of the darkness, but the abundance of light within the darkness. That people on the absolute brink of death — often marching quite literally to their death — still called for God’s salvation, still huddled together with their fellow human to provide a blanket for warmth, and still risked everything to bear witness for the rest of the world. In the bleakest possible circumstances, the human spirit is that intangible that can’t be squelched, denuded, deloused, or even killed. For certain, those who did not live to be liberated from the camps still have an enduring legacy for what they did while alive, and as a monument to the slogan, “Never again.” To ensure that such a mentality remains salient and its upholders vigilant rather than lapsing into hollow sloganeering, one needs to engage with and understand history — a history that is not all that long ago. In fact, nearly a quarter million Holocaust survivors are still alive across 90 countries. The Holocaust happened in a modern Western country across Europe, and the factors that led to it, enabled it, and turned a blind eye to it far beyond even the Nazi “Final Solution” machine, are factors that could arise in the hearts and psyches of humans again. It happened there; it could happen here, wherever your “here” is. That’s why any modicum of capitulation to would-be authoritarians, who prey upon base hatreds and fears for political power, is a nonstarter. “Never again” means never an inch to such people. Not now, not ever. Not here, not anywhere. All of this is a preamble to the fact of having visited today the Cincinnati Museum Center’s Auschwitz exhibit, with the appropriate subhead: Not long ago. Not far away.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Auschwitz exhibit is the commitment to solemnity its visitors abided by. Walking through the extensive exhibit, it was absolute silence unlike anything I’ve ever experienced, which only added to the weightiness of witness we were bearing witness to. The exhibit, which started in October and runs through April 2026, features more than 500 original artifacts from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland, the largest collection outside of Europe. Items include concrete posts that were part of the fence at the camp, fragments from prisoners’ barracks, a gas mask used by concentration officers, and most striking (reminiscent of Spielberg’s Schindler’s List with the bright red coat) is a red shoe amid the pile of shoes. Certainly then, the experience is visual and stark; as LIFE magazine said at the time about its decision to show the reality of Auschwitz: “Dead men have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them.” Which again goes back to the point of us bearing witness to the witness on display, no matter how hard it is to look at or hear. To the latter, the exhibit is also an extensive auditory experience. You carry an interactive audio handset that leads the way through nearly 40 audio experiences corresponding to different segments of the exhibit.

One logistical note before I continue: A museum employee said it would take someone about two hours to go through the entire exhibit. I’m not sure what that estimate is based upon. If you take the time to engage with all of the artifacts and their descriptions, listen to the aforementioned audio experiences, and watch a few non-audio videos, the time it took me to go through the exhibit was twice what they stated. In other words, at least four hours, and honestly, I could see it going even longer. I mention that only for your planning purposes and/or so you know what to expect. Any museum should be given adequate time to explore it, but something of this magnitude and resonance? You need to take your time. Before I continue, one other aside. When my grandpa died, I wrote about the flummoxing dichotomy of his death versus the need for the family to eat immediately after. I experienced that same feeling today during the exhibit. I was 60 percent of the way through (the exhibit has various markers like that) when I decided to turn back for lunch, eat, and then finish the rest of the exhibit. It just felt … wrong. Nonetheless, it also served as a worthwhile momentary reprieve from the heaviness of it all.

Many people who have engaged with the Holocaust before are likely familiar with Hannah Arendt and her report on the “banality of evil” regarding the Nazis. That is the case with the exhibit, evidenced by one of the first quotes you encounter from Franz Novak, a Gestapo official who coordinated the deportation trains to Auschwitz, in a statement given in his postwar trial in 1965, “For me, Auschwitz was just a railway station.” While this mass accosting, rounding-up, disappearing, and killing of Jews across Europe was occurring, its perpetrators and enablers largely seemed to view it as banal bureaucratic exercise, or rather, they transformed it into one, a “machinery of death.” As I’ll talk about later, the guards and such, frolicked and smiled and lived happy lives within spitting distance of the crematoriums of Auschwitz, where up to 4,000 bodies could be turned to ash on a daily basis.

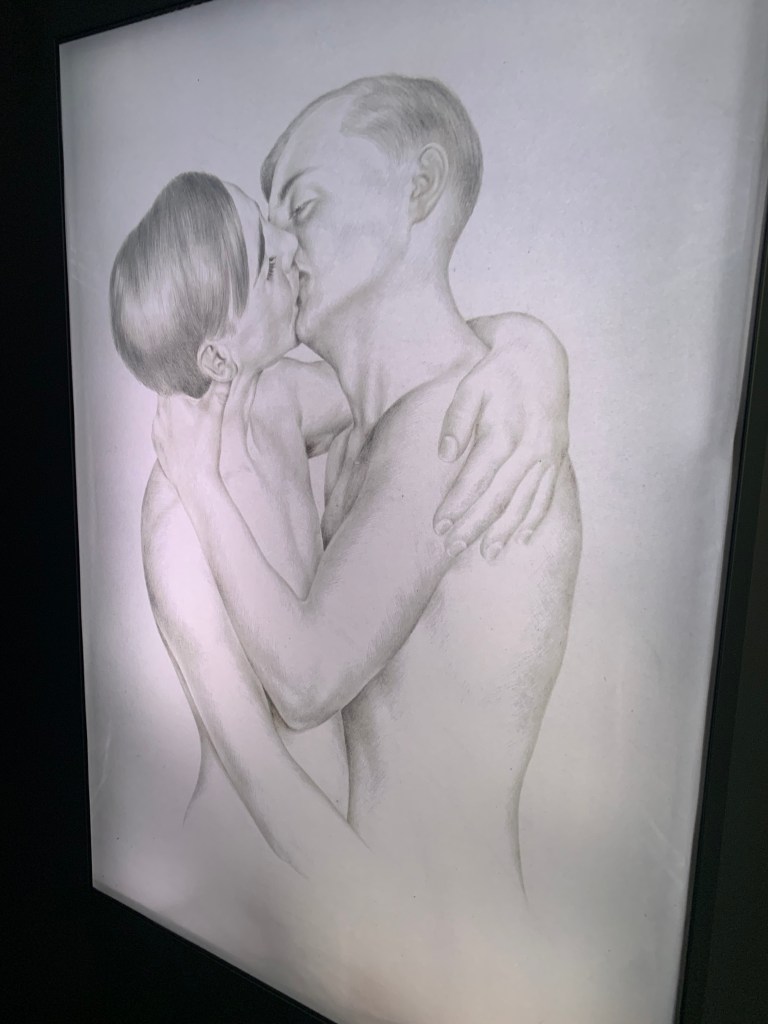

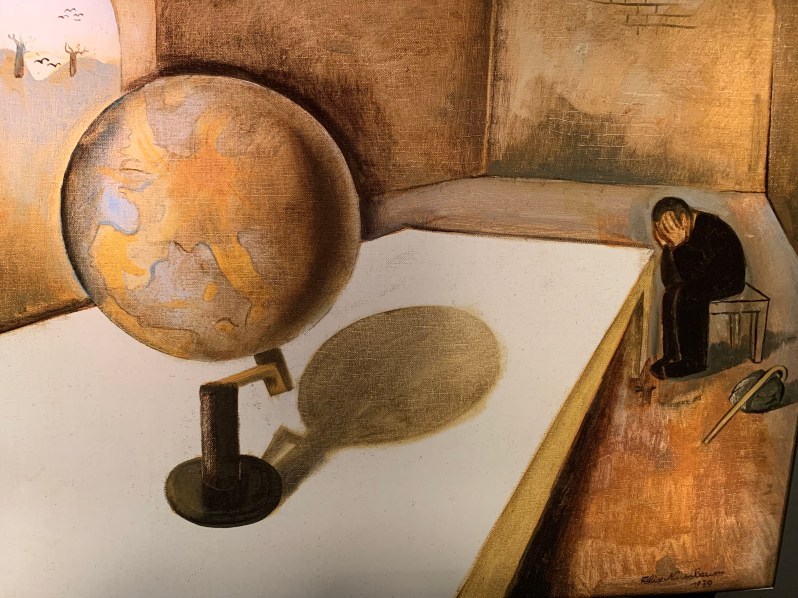

To understand how the Holocaust came to be, though, the exhibit takes visitors through the run-up the 1930s with the aftermath of WWI, the punishing (for Germany) Treaty of Versailles, and the Weimar Republic years before Hitler ascended to power in 1933 and quickly turned Germany into a dictatorship. One of the interesting tidbits from the Weimar Republic years was that some Germans saw it as a time of “opportunity and innovation.” Artist Richard Grune, a gay man, founded a democratic, self-governing camp for working-class children. Unfortunately, he was arrested for being gay and spent 11 years in prison. The reason I find it interesting is you don’t often hear about the positives of the Weimar Republic, although that story had a negative ending. As another example, Christian Schad was an artist during the time who explored “homoerotic themes, reflecting a period of cultural openness.” Pictured below is one of his drawings on display.

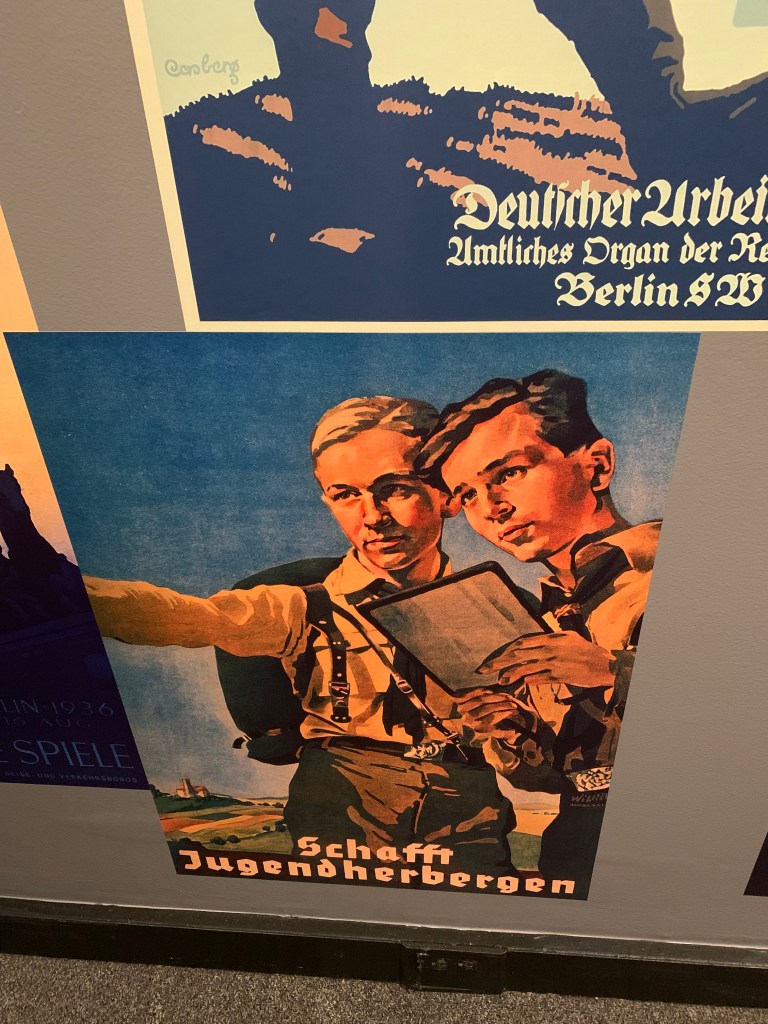

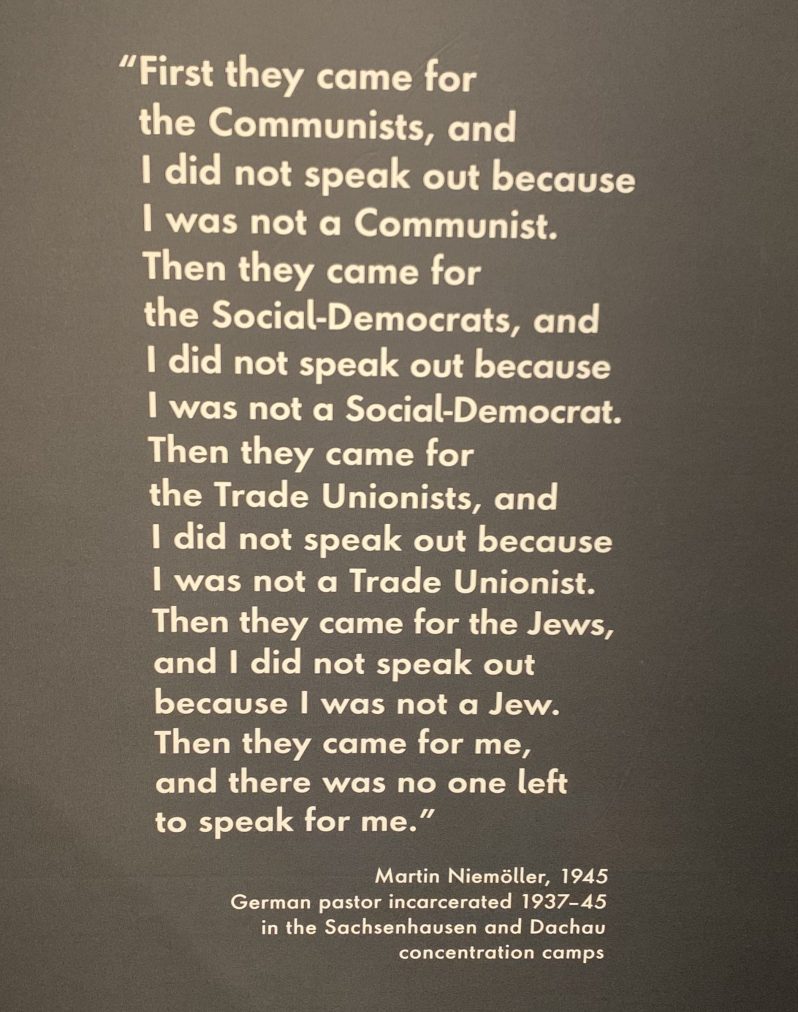

Such openness became unacceptable, of course, under Nazism because of their distorted ideal of masculinity. It’s so interesting how many would-be authoritarians and actual authoritarians throughout the years have not only rose to power on the basis of stirring up nationalistic hatred and fear, but their authoritarianism is tied up into a distorted view and understanding of masculinity. Indeed, as Nazi propaganda featured in the exhibit shows, the Nazis sought to unify the German people around a particular image of themselves and the way forward, one completely extricated from “Jewish influence.” The corollary to having an idealized, propagandized view of the German people, is that anyone who did not meet that standard were marked as undesirables and the German state must rectify that. So, the pogrom against the Jews was preceded by rounding up political prisoners of the Nazis into concentration camps, then the homeless, homosexuals, certainly, those deemed mentally disturbed, and those with disabilities. The Roma and Sinti people were imprisoned because they were considered “genetically criminal,” which is a stigma still associated with them. Those considered communists weren’t immune, either. Finally, one target of Nazi ire I wasn’t as familiar with until today were the Afro-Germans, which are Germans of African descent. One of the featured examples of this was Theodor Wonja Michael, who was born in 1925 in Berlin to a white German mother and a Cameroonian father. He was imprisoned in a camp because of the color of his skin. Inadvertently, as he talks about in a video, it may have saved him from having to join the Hitler Youth, as they wouldn’t accept him. (By the way, again, we talk about the Holocaust not being that long ago, Michael just passed away in 2019.) In other words, whole communities began to be infiltrated and attacked to clear out the “undesirables.” Raimund Pretzel (aka Sebastian Hoffner), a German author writing from exile in Britain in 1938, captured the sentiment: “More unnerving was the disappearance of a number of quite harmless people who had in one way or another been part of daily life. One did not know whether they were dead, incarcerated, or had gone abroad. They were just missing.”

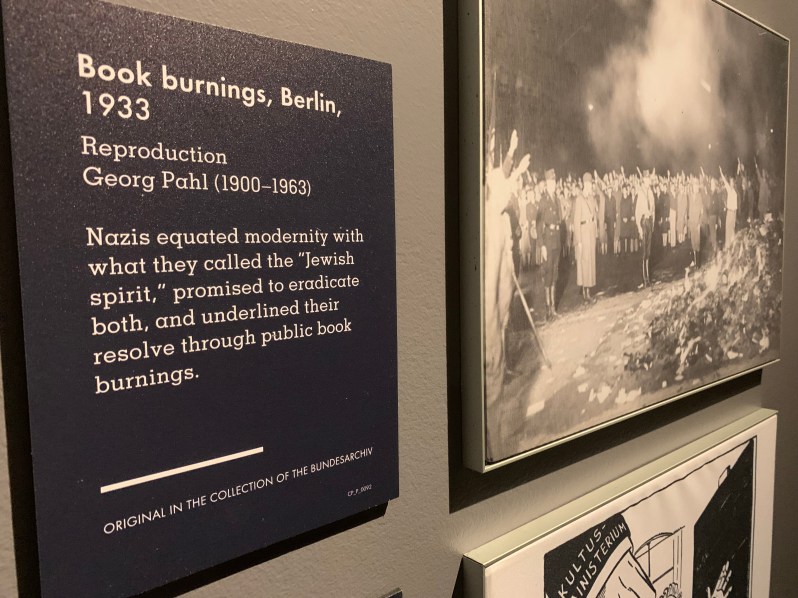

Nazism didn’t just have a problem with cultural openness contradicting their idealized, distorted view of masculinity, but they also had a problem with modernity as a whole: the elites from scientists to intellectuals. This, of course, meant book burnings occurred in Berlin under Nazi auspices. The reason being, modernity was equated with the “Jewish spirit.”

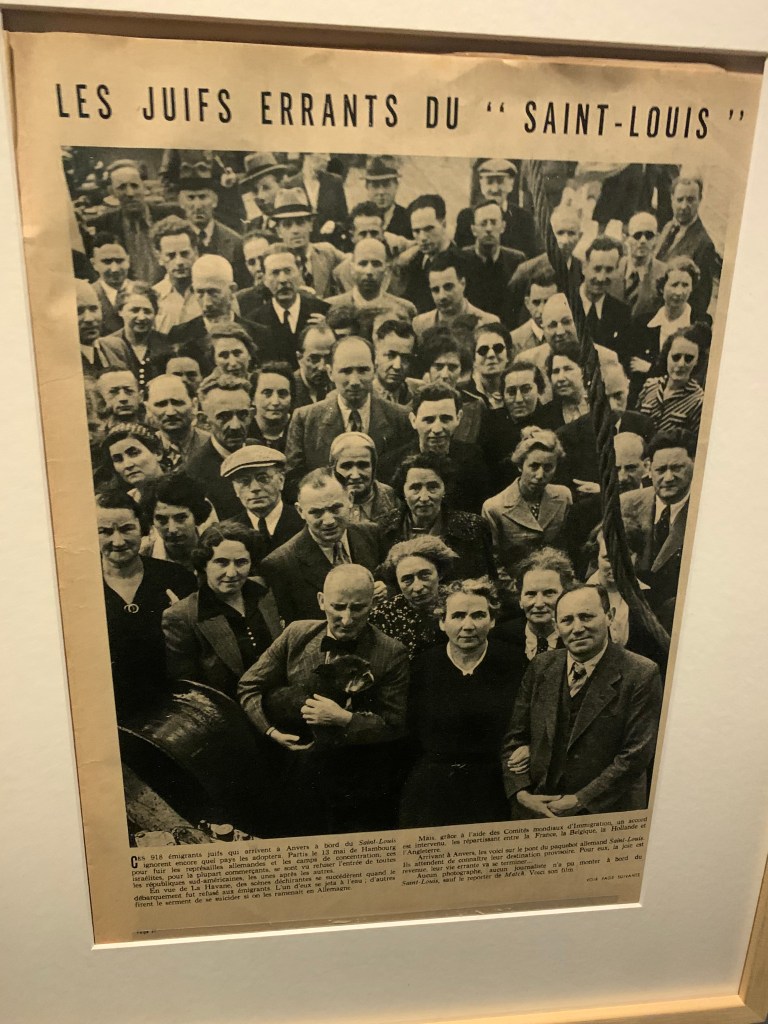

As the exhibit reminds us throughout, and especially at the end, a genocide cannot be carried out by one charismatic man in Hitler. It took scores of people underneath him and throughout Germany and Europe to make it possible. But also, it took collaborators like the Vichy government in France or the Hungarian government, more than happy to send Jews into Nazi hands in exchange for money. America and Britain aren’t immune from this, either. Infamously, in 1939, America turned away the St. Louis carrying 937 Jews looking for refuge in America. At least 254 of the passengers are thought to have died in the Holocaust. That’s one of the ugliest stains on modern America, and again, a clarion call that reverberates to today: we ought to be a refuge for all the world’s refugees and those fleeing horrors from other countries, not closing our doors dismissively and fearfully. Britain, for its part during the same time period, lowered the number of Jews able to flee to Palestine to 15,000 annually, I believe.

“There are now two sorts of countries in the world, those that want to expel the Jew and those that don’t want to admit them.” – Chaim Weizman, 1936, President, Zionist Organization

Returning to the banality of evil point, it isn’t to absolve the Nazis by any measure. That the mass slaughter of Jews became such a bureaucratic machine doesn’t mean there weren’t those enthusiastically cheering on such slaughter. In one of the most haunting moments of the exhibit, we hear a snippet from Hitler’s 1939 “Prophecy as Threat” speech to the Greater German Reichstag (legislature) on the sixth anniversary of his appointment as chancellor, where with invective, he stated, “We will annihilate the Jewish race from the Earth.” The chilling part wasn’t that statement, which one would expect to hear from Hitler, but that everyone hearing it in the legislature cheered uproariously. Such cheering haunts me, and again, speaks to Hitler not able to carry out the genocide of the Jews alone. But I’d remiss if I didn’t point out how Rudolf Höss exemplified Arendt’s “banality of evil.” Höss was the commandant of Auschwitz and his home was located adjacent to the prisoner compound. There’s one picture in the exhibit of his family enjoying their time in the garden. In fact, Höss boasts about the garden and its joys and how he’s given everything to his wife. It made me wonder about his wife and children and what became of them (Höss was executed after the war). Three of the five children went on to live long lives, two of them well into the 21st century. Another “banality of evil” one cannot overlook is that of IG Farben, a rubber and oil company that literally set up a plant at Auschwitz, and used Jewish slave labor. While the Allies disbanded the company in 1945, it doesn’t seem clear to me any of the directors faced true justice despite some being convicted at the Nuremberg Trials. Or there’s Topf and Sons, which was the engineering company that manufactured the ovens at Auschwitz. Their executives didn’t even make it to Nuremberg.

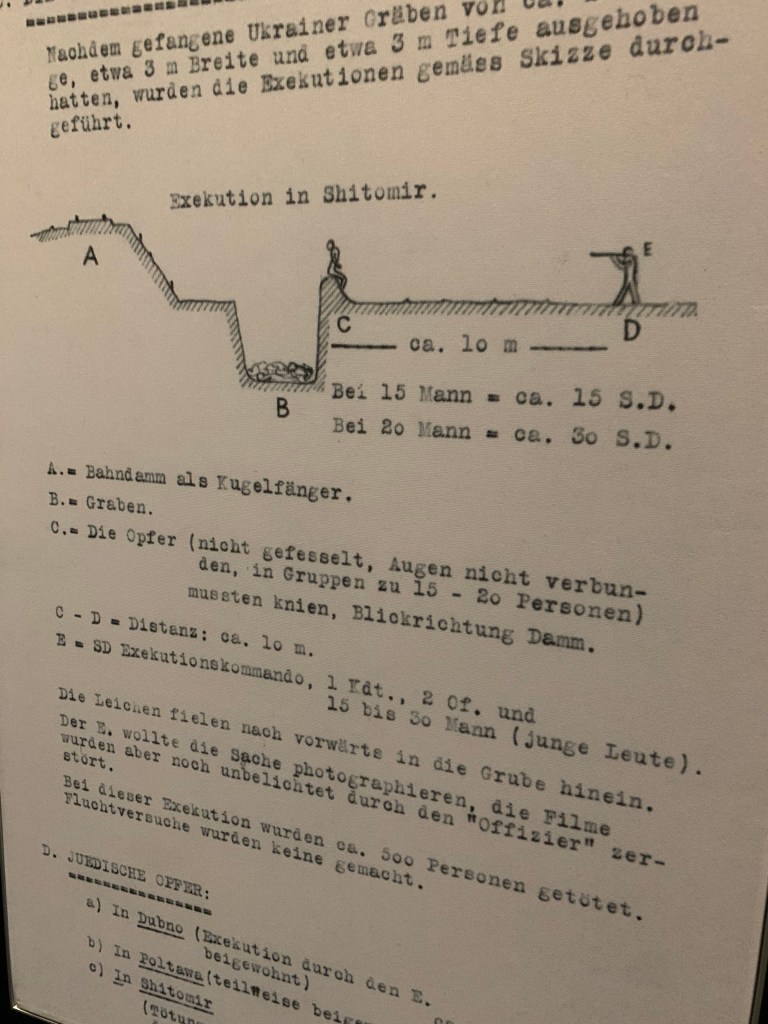

When I talk about the bureaucratic machinery of death, it’s quite literal. One of the most startling artifacts from the exhibit is a diagram of shooting procedure from 1942, which illustrates that murder procedures were standardized across the SS, and thousands were killed by bullets. There’s also a short video of such executions, with dozens of witnesses, including randomly a dog, and a rather bored seeming executioner smoking a cigarette. Another horrific aspect of the exhibit was the matter-of-fact way children were executed. A shoe with a sock still tucked inside of it is an artifact left behind now as a testament to such cruelty.

In 2004, Oskar Gröning, a SS man at Auschwitz (who only just died in 2018!), explained why he condoned the killing of children: “The children, they’re not the enemy at the moment. The enemy is the blood inside them. The enemy is the growing up to be a Jew that could become dangerous. And because of that the children were included as well.” Sickening and appalling. One also can’t discuss the Holocaust without talking about Dr. Josef Mengele and his medical experiments, particularly on twins. Auschwitz proved a rare opportunity for the sociopath: twins dying at the same time so he could conduct autopsies on their bodies and uncover the origin of various diseases.

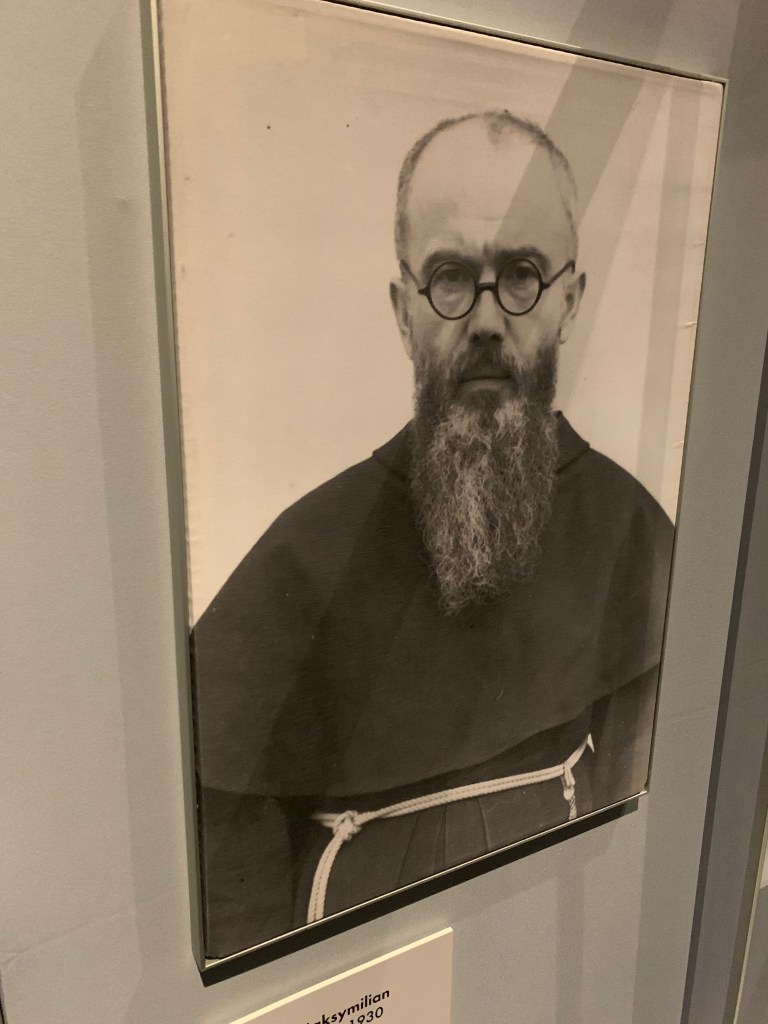

But I also talked about that indominable spirit of humanity, that unyielding intangible. One of my favorite stories of resistance during the Holocaust that represents this is that of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a village in southeastern France. It’s about French Protestants who saved Jews during the Holocaust led by Pastor André Trocmé. If there’s not a movie about Pastor André Trocmé and his heroism, I need it. It wasn’t just him, though, as the exhibit reminds us, “it takes a village.” Just as it “takes a village” to carry out a genocide, so, too, does it take a village to resist one. I wrote more about the village in a book review here. Resistance happened within Auschwitz as well, which is astounding to consider. One wall description noted the reason for “persistence and resistance”: “Resistance was expressed in the determination that — despite the best efforts of the SS — death in Auschwitz would not remain anonymous, and the victims would be named.” One incredible example of this was Maksymiliam Maria Kolbe, a Polish priest, a prisoner of the camp. He secretly heard confessions and encouraged others to pray despite it being prohibited. Two months after arriving, he volunteered to die in place of another inmate, Franciszek Gajowniczek, who had been sentenced to death by starvation. Kolbe was killed by the Nazis after starvation efforts failed, but Gajowniczek survived the war. Kolbe was declared a saint as a martyr by the Catholic Church in 1982. Perhaps the story that gave me the widest grin for its defiance was that of Róża Robota, who recruited women prisoners to revolt in the summer of 1944. The Nazi backlash to the uprising resulted in the death of nearly 500 people, including Robota, who was hanged publicly. As the noose was placed around her neck, she cried out, “Nekama!” (Revenge!). Bad-ass. Another one was Rivka Liebeskind, in protecting a fellow prisoner also named Rivka, who gave her a pocket knife (a featured artifact in the exhibit) and advised her, “If you get sent to the gas chambers, stab a Nazi before you go to your death.” I marvel at such people like Robota and Liebeskind. Their persistence and resistance and defiance is the best of humanity juxtaposed to the worst of humanity.

Finally, there is a Cincinnati connection to the exhibit and the Holocaust. Some of the Auschwitz survivors rebuilt their lives in Cincinnati. Indeed, 70 percent of Cincinnati’s 1,000 Holocaust survivors arrived right at the site of the Cincinnati Museum Center via Union Terminal.

“I arrived in Cincinnati at Union Terminal with a wife, a baby, and a suitcase. And that ended the first part of my life.” – Werner Coppel, Auschwitz survivor

Coppel, quoted above, survived a Nazi death march, which occurred when Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and one of the biggest perpetrators of the Holocaust, tried to hide the surviving prisoners of Auschwitz deeper inside Germany against advancing Allies and made those prisoners walk an unimaginably long distance. Coppel convalesced in Berlin after the war and married the nurse who helped him, Trudy Sibermann. Coppel and Sibermann married in 1946, the first post-war Jewish wedding in Berlin. Talk about a nice defiant mark on the scorch of Nazism! Two years later is when the couple, along with their infant son, came to Cincinnati. The suitcase Coppel brought is an artifact on display.

Why do we remember? Why is it important? Why spend four hours on a Sunday going through the Auschwitz exhibit at the Cincinnati Museum Center? Piotr Cywiński, director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum stated it best, “Remembrance has helped us shape the post-war world. Today, we witness how our efforts to build a more just and humane world are under threat. We remember, so we are aware of what we must protect and nurture. Remembering gives us an awareness of what none of us can remain indifferent to.”

To remain indifferent in an age of injustice is to be a collaborator. So it was true then and so it is now. And so it will always be.

One coda to all of this I wrote shortly after already publishing this post: At the top, I talked about how “any modicum of capitulation to would-be authoritarians, who prey upon base hatreds and fears for political power, is a nonstarter.” Let me expanded upon that. I have an incredibly difficult time understanding how anyone could give a demagogue like Trump — who plays on those aforementioned base hatreds and fears to demonize all manner of “others,” including refugees, immigrants, Blacks, the LGBTQI+ community, women, and so on, to amass more power and wealth off of the presidency — that inch. He’s taken that inch to bring everything that has made America actually great (for all our faults, historical and modern, being a “shining city on a hill” for the world, rule of law, fidelity to democratic norms, etc.) to the brink. None of what’s happening from bringing the military into our cities to the unaccountable violence of ICE to bombing and killing suspected drug smugglers on Venezuelan boats to flouting court orders to usurping Congressional authority is right. Being a mean bully isn’t right. It’s not right for my neighbor or coworker, and it’s not right for the most powerful person on the planet. It astounds me people who disdain bullies defend the most powerful and odious of bullies. Trump is not Hitler. But he is a would-be authoritarian playing on fears of the other and who expects total capitulation from citizens, politicians, businesses, and other world leaders. It’s grotesque and unAmerican. A Ronald Reagan appointed judge recently stepped down, explaining he could no longer bear to be restrained by what judges can say publicly or do outside the courtroom. He added, “The White House‘s assault on the rule of law is so deeply disturbing to me that I feel compelled to speak out. Silence, for me, is now intolerable.” My “now” was the moment Trump came down the escalator in 2015, but point taken. Everything is too damn intolerable to remain silent — to remain indifferent.

One thought