Spoilers!

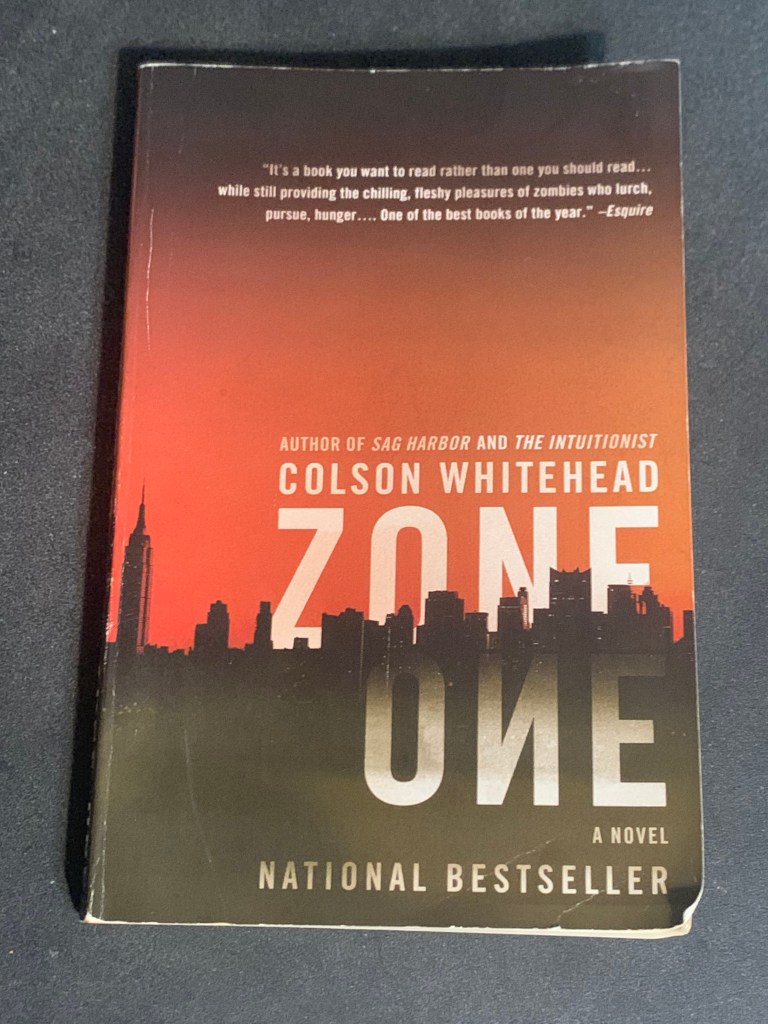

Maybe when the zombie hordes come, it is the average, B-level person who survives from one human settlement to the next. At least that’s the case in Colson Whitehead’s 2011 book, Zone One, about the zombie apocalypse, which I also took as an ode to New York City. Told from Friday to Sunday, the main protagonist, Mark Spitz — a “nickname” taken from the 1972 Munich Olympian in swimming, while also belying the racial stereotype of Black-men-can’t-swim — and his Omega unit are part of the reconstruction effort in New York City, rechristened Zone One. Because of his self-admitted averageness, Mark Spitz moves (swims!) through the end of the world more clear-eyed than most and more ready than most to move on to the next thing, should this current arrangement fall, and inevitably, it will. That has always been a fascinating aspect about any apocalyptic stories to me: why continue on? What’s the impetus in a dead world to keep fighting against the dying of the light? The same impetus that keeps most going during the pre-times.

Since every author likes to have their own term for zombies, Whitehead’s term is “skels.” But interestingly, and different than anything I’ve read in the zombie genre prior, there are stragglers who constitute 1 percent of the skels. These are zombies who are, well, melancholy, and not dangerous. They just stand around in a place seemingly of some prior significance to them gazing upon whatever their dead-but-reanimated-brains are seeing. They are not after entrails, but are abating entropy, nonetheless. Mark Spitz’s job specifically, with his Omega cohorts Kaitlyn and Gary, is as “sweepers” going through various buildings in New York City ensuring they’re clear of skels. It’s a big operation: if they find one, they drop ’em, tag ’em, bag ’em, and then there’s a whole separate part of the operation where the skels are incinerated. Because of that incineration process, Mark Spitz routinely references the falling “ash” and how it feels glommed on to him at this point. I thought it was amusing the first skels the Omega team encounters at the start of the book during a routine sweep were members of the office’s human resources team — I don’t know if Whitehead was making a commentary or not, but amusing anyhow.

Inevitably, at the end of the world, there is going to be those who try to restart the world, kickstart the engine of life. In Zone One, that’s Buffalo. Buffalo is the epicenter of reclaiming the old world. There’s a great deal of PR going on to massage the truth, of course, that kickstarting the old war is far more tenuous than they are letting on. The propagandists have a term for what the survivors are: American Phoenixes, or pheenies. Even at the end of the world, there are sponsors of cigarettes and such. Heck, Gary still believes in the American dream! The American dream has not died; he’s hoping to patent some skel-capturing device. Unfortunately for Gary, he plays around too much with what he thinks is a fortune-telling straggler, who instead bites his thumb off. And also in Buffalo is a fancy-schmancy psychologist who states the obvious about what all the survivors are experiencing: PASD, or post-apocalyptic stress disorder. PASD just manifests differently for people, same as PTSD in the old world.

Even though the book is only told across three days, we travel back with Mark Spitz through the “Last Night,” as it’s called, when the old world fell into the end of the world. (It reminded me of COVID-19, how we all collectively recognized Tom Hanks contracting COVID and NBA games being canceled on the same weekend as the shit-hitting-the-fan moment for our pandemic.) He came home from gambling with a friend to find his mother gnawing on his father, which itself was reminiscent of a childhood memory of coming in on them engaging in a sexual act. Talk about a tangled mess of PASD! But there’s also Mim, who became his post-apocalyptic girlfriend while they stayed holed up in a toy store. Then, one day, she went out for some supplies and never came back. So it happens, and so Mark Spitz keeps it moving. The melancholy inherent in Mark Spitz’s story is not so much his self-admitted averageness, but that he necessarily enacts his own internal barricade — detachment — from the end of the world. To burrow too deep into the messiness of it all would render him a straggler of sorts. Or be like the Lieutenant, who blows himself up with a grenade.

Speaking of barricades, Zone One ends with Zone One’s barricade failing, as it inevitably always does, and New York City being flooded with skels. Mark Spitz is able to escape the initial melee, and seems ready to live up to his nickname of swimming to well, not safety, but whatever is next.

I love when an author brings their considerable prowess to bear upon genre fiction, as Whitehead’s done here with the zombie genre. It was introspective, thought-provoking about how fragile this world actually is from tipping over into the end of the world, and again, melancholic in its aching for all that is nevertheless beautiful about this world we’ve created. It’s cliche at this point to say, but it’s true: the best zombie books are not about zombies, but about the humans trying to survive, and on that score, Mark Spitz was a compelling, neurotic character to follow, despite his claims to averageness.